A Meticulous Guide to Advances in Deep Learning Efficiency over the Years

A very long and thorough guide how deep learning algorithms, hardware, libraries, compilers, and more have become more efficient.

This post offers a comprehensive and chronological guide to advances in deep learning from the perspective of efficiency: things like clusters, individual hardware, deep learning libraries, compilers — even architectural changes. This post is not a survey paper, and is intended to provide the reader with broader intuition about this field — it would be impossible to include every little detail that has emerged throughout the last 40 years. The posted X thread https://x.com/a1zhang/status/1851963904491950132 also has a very high-level summary of what to expect!

Preface. The field of deep learning has flourished in the past decade to the point where it is hard as both a researcher and a student to keep track of what is going on. Sometimes, I even find it hard to keep track of the actual direction of the field. In a field that often feels hand-wavy and where many methods and results feel lackluster in practice, I wanted to at least get a sense for progress in how we got to where we are now.

I wanted to write this post in a narrative form — to 1) be digestible to the reader rather than an information dump, and 2) allow the reader to view the field from a macroscopic lens and understand why the field moved the way it did. I have tried to be as paper-focused as possible (similar to Lilian Weng style blogs!) and include as many landmark (or just cool) works as I saw fit; if the reader feels something should be included or edited, please let me know

- NVIDIA’s newest Blackwell B200 GPU is estimated to cost 30k - 40k USD.

- For FP8

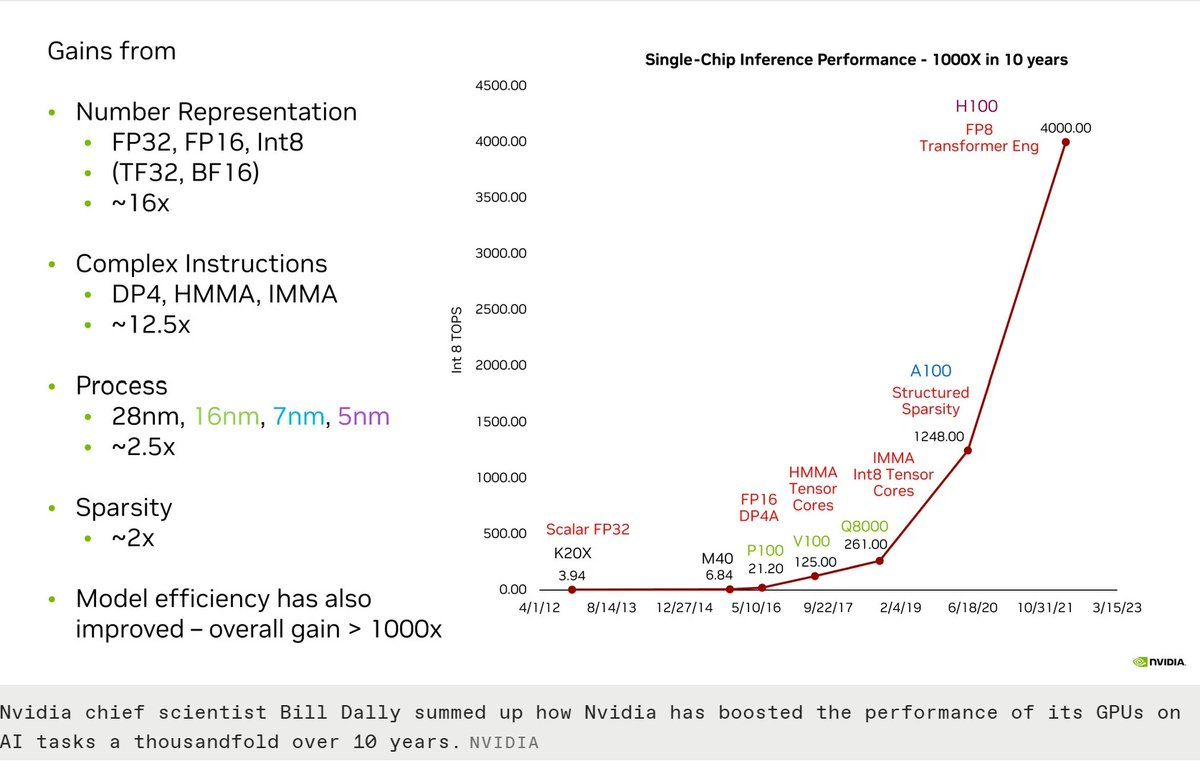

Recent NVIDIA hardware includes specialized “tensor cores” that can compute matrix multiplication on 8-bit floating point numbers really fast. , it can achieve up to ~4500 TeraFLOPSFLOPS means floating-point operations per second, which is a metric for roughly how fast a processor or algorithm is because most operations in deep learning are over floating point numbers. , which is absolutely insane! - It features 192GB of high-bandwidth memory / DRAM, which is the main GPU memory.

- For FP8

-

Llama 3.1 405B, Meta’s latest open-source language model is 405B parameters (~800GB).

- It was trained on a whopping 16k NVIDIA H100s (sitting on their 24k GPU cluster)

- It’s training dataset was 15 trillion tokens.

Part I. The Beginning (1980s-2011)

The true beginning of deep learning is hotly contested, but I, somewhat arbitrarily, thought it was best to begin with the first usage of backpropagation for deep learning: Yann Lecun’s CNN on a handwritten digits dataset in 1989

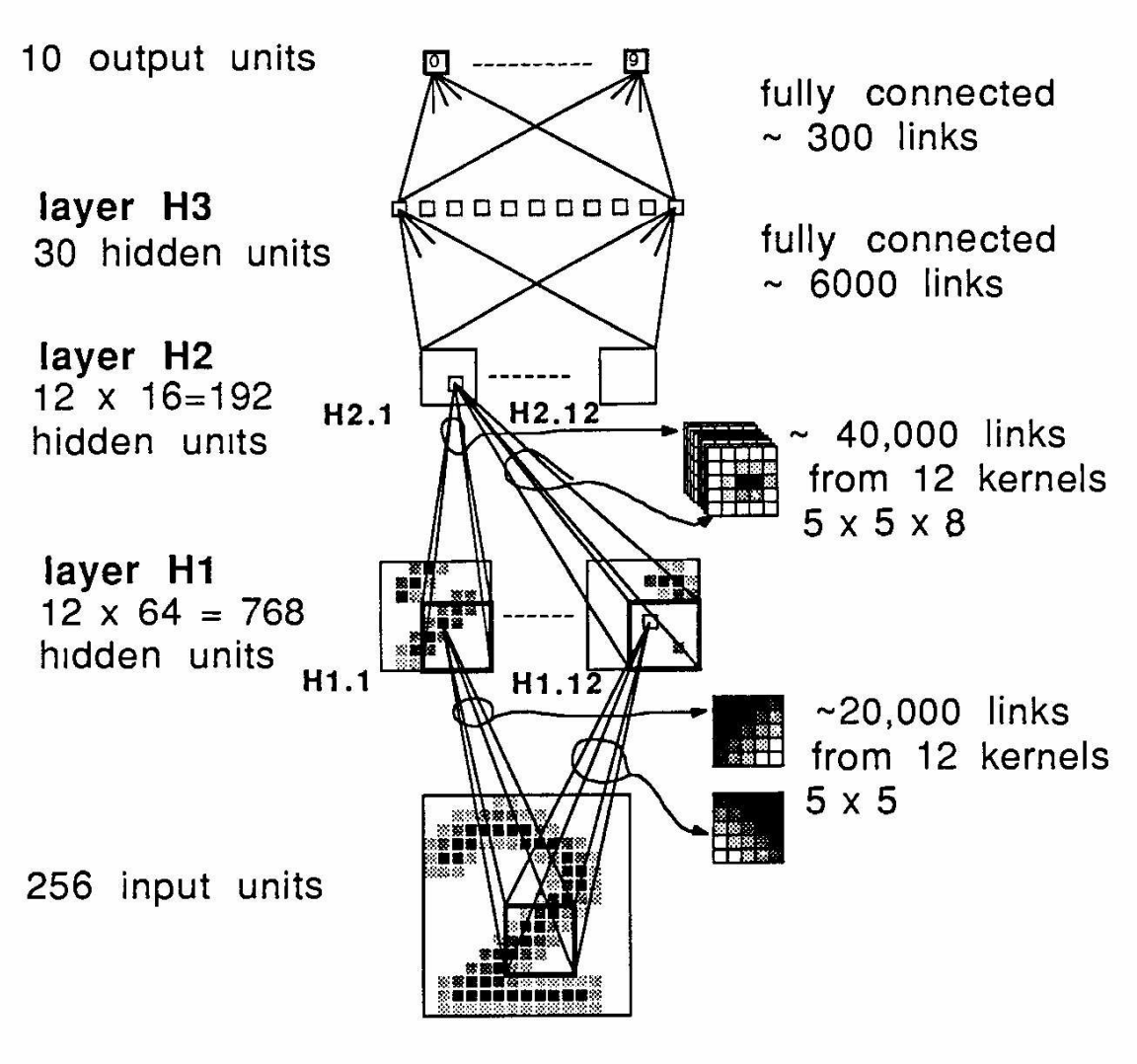

Backpropagation Applied to Handwritten Zip Code Recognition (Lecun, 1989

Andrej Karpathy has a wonderful blog that attempts to reproduce this paper on modern deep learning libraries with some extra numbers for reference:

- The original model contains roughly 9760 learnable parameters, 64K MACs

MAC stands for multiplication-accumulate, which is a common metric for GPUs because they have fused multiply-and-adder instructions for common linear algebra operations , and 1K activations in one forward pass. - On his Macbook M1 CPU, he trains a roughly equivalent setup in 90 seconds — it goes to show how far the field has progressed!

Some other notable works at the time were the Long Short-Term Memory (1997)

I.1. Existing Fast Linear Algebra Methods

The introduction of the graphics processors in the late 20th century did not immediately accelerate progress in the deep learning community. While we know GPUs and other parallel processors as the primary workhorse of modern deep learning applications, they were originally designed for efficiently rendering polygons and textures in 3D games — for example, if you look at the design of the NVIDIA GeForce 256 (1999), you’ll notice a distinct lack of modern components like shared memory

Programming a GPU in the 2000s. By this point the CUDA ecosystem had not matured, so the common method for hacking GPUs for general purpose applications was to configure DirectX or OpenGL, the popular graphics APIs at the time, to perform some rendering operation that involved say a matrix multiplication.

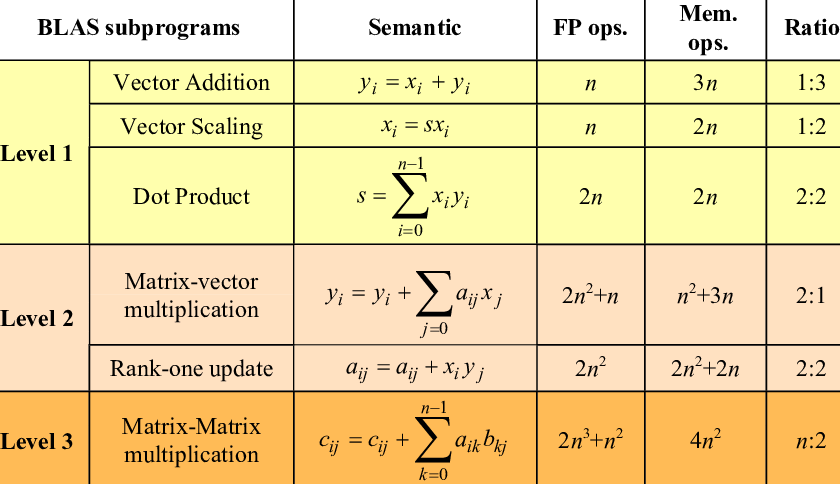

Linear Algebra on a CPU. During this time, a suite of libraries had emerged in parallel for computing and solving common linear algebra paradigms like matrix multiplication, vector addition, dot products, etc. Many of these libraries used or were built off of the BLAS (Basic Linear Algebra Subprograms) specification with bindings for C and Fortran. BLAS divides its routines into three levels, mainly based on their runtime complexity (e.g. level 2 contains matrix-vector operations, which are quadratic with respect to the dimension). On CPUs, these libraries take advantage of SIMD / vectorization

- LAPACK (1992): The Linear Algebra Package provides implementations of common linear algebra solvers like eigendecomposition and linear least squares.

- Intel MKL (1994): The Intel Math Kernel Library is a closed-source library for performing BLAS (now other) operations on x86 CPUs.

- OpenBLAS (2011): An open-source version of Intel MKL with similar, but worse, performance on most Intel instruction-set architectures (ISAs).

- OpenCL (2009): An alternative to hacking in OpenGL, OpenCL was a device-agnostic library for performing computations in multiple processors. It was far more flexible for implementing primitives like matrix multiplication.

Just for some reference numbers, I just ran a simple matrix multiplication experiment on my Macbook M2 Pro (12-core CPU, 3.5 GHz) with NumPy 1.26.4, which currently uses OpenBLAS under the hood. I found this blogpost by Aman Salykov which does more extensive experimenting as well.

> Average of 361.4851 GFLOPS

I.2. Compute Unified Device Architecture (CUDA), 2006

I really like this post by Fabien Sanglard, which explains the history and motivating design patterns of CUDA and NVIDIA GPUs starting from the Tesla architecture over the years.

CUDA was originally designed to enable parallel programmers to work with GPUs without having to deal with graphics APIs. The release of CUDA also came with the release of the NVIDIA Tesla microarchitecture, featuring streaming multiprocessors (SMs), which is the standard abstraction for “GPU cores” used today (this is super important for later!). I’m not an expert in GPU hardware design (actually I’m not an expert in anything for that matter), but the basic idea is that instead of having a lot of complicated hardware units performing specific vectorized tasks, we can divide up computation into general purpose cores (the SMs) that are instead SIMT (single-instruction multiple threads). While this design change was meant for graphics programmers, it eventually made NVIDIA GPUs more flexible for generic scientific workloads.

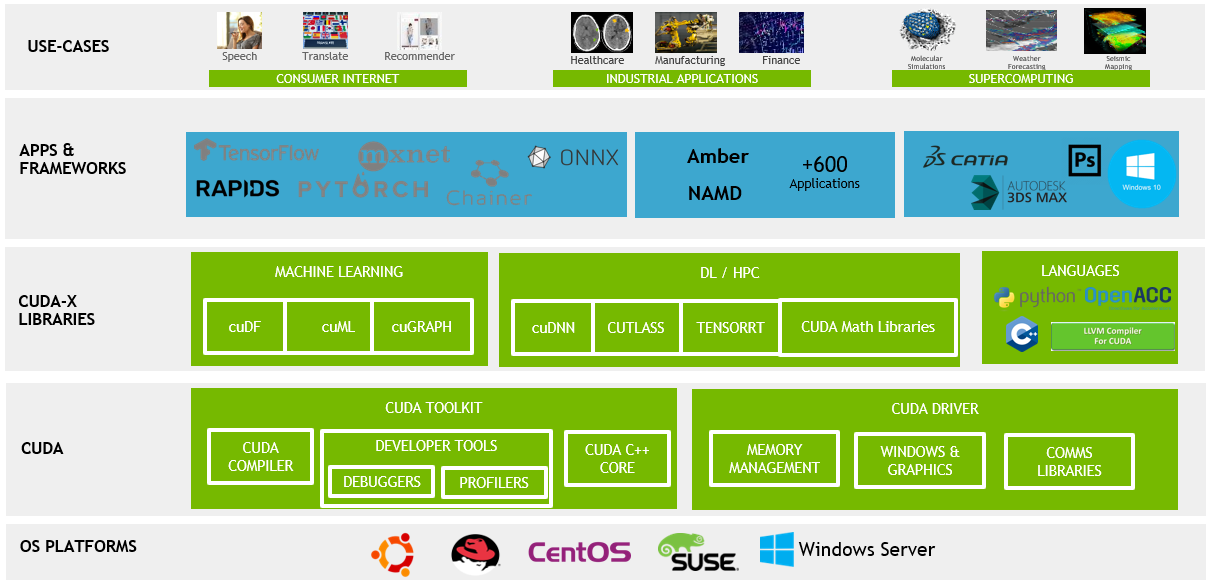

Nowadays, CUDA has evolved beyond just a C API to include several NVIDIA-supported libraries for various workloads. Many recent changes target maximizing tensor core usage, which are specialized cores for fast generalized matrix multiplication (GEMM) in a single cycle. If what I’m saying makes no sense, don’t worry — I will talk more extensively about tensor cores and roughly how CUDA is used with NVIDIA GPUs in the next section.

Some notable libraries that I’ve used in practice are:

- cuBLAS (Introduced in CUDA 8.0): The CUDA API for BLAS primitives.

- cuDNN: The CUDA API for standard deep learning operations (e.g. softmax, activation functions, convolutions, etc.).

- CUTLASS (Introduced in CUDA 9.0): A template abstraction (CuTe layouts) for implementing GEMM for your own kernels — doesn’t have the large overhead of CuBLAS/CuDNN, which supports a wide variety of operations.

- cuSPARSE (Introduced in CUDA 8.0): Efficient linear algebra operations on different kinds of sparse storage formats like coordinate format (COO) and compressed sparse row (CSR).

Part II: Oh s***— Deep learning works! (2012-2020)

Although this section roughly covers the 2010s, many modern methods were derived from works during this time, so you may find some newer techniques mentioned in this section because it felt more natural.

While classical techniques in machine learning and statistics (e.g. SVM, boosting, tree-based methods, kernel-based methods) had been showing promise in a variety of fields such as data science, a lot of people initially did not believe in deep learning. There were definitely people working in the field by the early 2010s, but the pre-dominant experiments were considered more “proof-of-concept”. At the time, classical techniques in fields like computer vision (e.g. SIFT features, edge detectors) and machine translation were thought to be considerably better than any deep-learning methods. That is, until 2012, when team SuperVision dominated every other carefully crafted computer vision technique by an absurd margin.

Part II.1: The first breakthrough on images!

ImageNet, 2009. In 2009, the ImageNet dataset (shout-out to Prof. Kai Li, the co-PI, who is now my advisor at Princeton) was released as “the” canonical visual object recognition benchmark. The dataset itself included over 14 million annotated images with >20k unique classes, and represented the largest annotated image dataset to date. The following is a snippet of 2012 leaderboard for top-5 image classification, where the model is allowed 5 guesses for each image.

ImageNet ILSVRC 2012 Leaderboard for classification, first and second place teams.

| Team | Accuracy (top-5 predictions) |

|---|---|

| SuperVision (AlexNet) | 84.69% ▴ |

| ISI (Fisher vectors) | 73.83% |

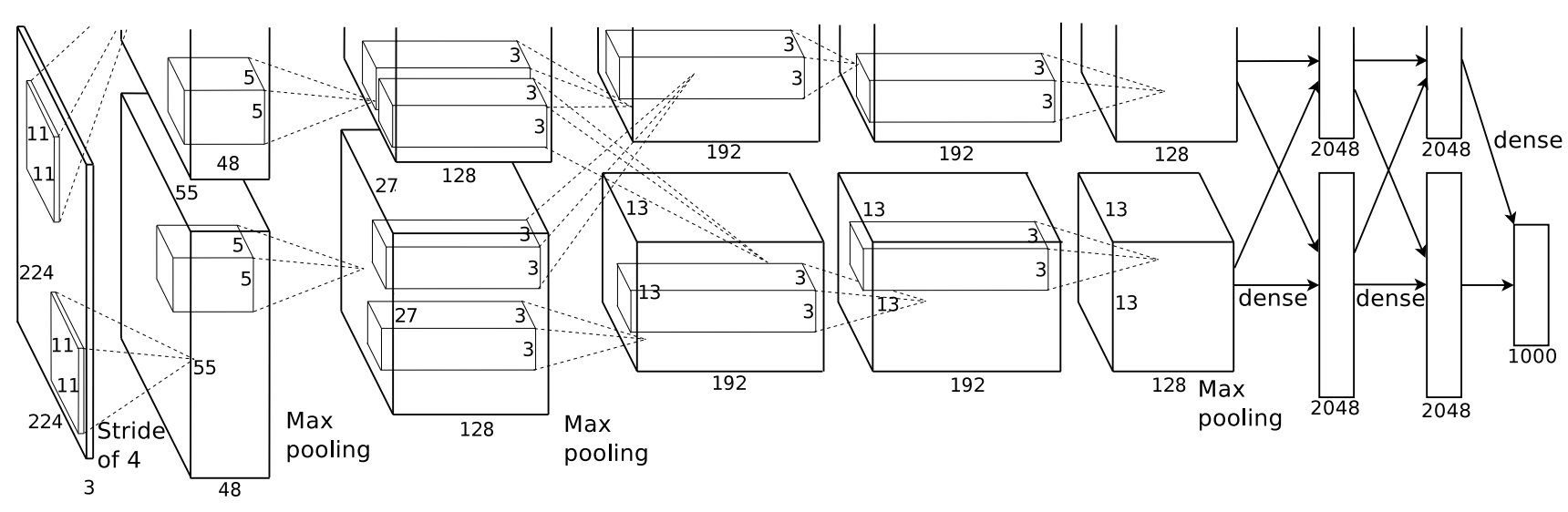

AlexNet (Krizhevsky et al., 2012

- The original source code in CUDA C++ can be found on Google Code Archive.

- I came across this GitHub repository by user

albaniethat estimates the throughput of AlexNet’s forward pass to be ~700 MFLOPS, but I’m not sure where they got this runtime estimate from or what hardware it was run on. Regardless, it is most likely an upper-bound for the actual performance.

DanNet (Cireşan, 2011

Remark. Interestingly, I found from this Sebastian Raschka blog that there were several other works that had adapted deep neural networks on GPUs. Nonetheless, none of these works had implemented a general-enough method to efficiently scale up the training of a convolutional neural network on the available hardware.

Part II.2: Deep learning frameworks emerge

So it’s 2012, and Alex Krizhevsky, a GPU wizard, has proven that we can successfully use deep learning to blow out the competition on a serious task. As a community, the obvious next step is to build out the infrastructure for deep learning applications so you don’t need to be a GPU wizard to use these tools.

Theano (2012)

Caffe (2013). Developed at UC Berkeley, Caffe was an older, high-performance library for developing neural networks in C/C++. Models are defined in configuration files, and the focus on performance allowed developers to easily deploy on low-cost machines like edge devices and mobile. Eventually, a lot of features in Caffe/Caffe2 were merged into PyTorch, and by this point it’s rarely directly used.

TensorFlow v1 (2015). Google’s deep learning library targeted Python applications, and felt far more flexible far dealing with the annoying quirks of tensors

Torch (2002) —> PyTorch (2016). Torch was originally a linear algebra library for Lua, but eventually it evolved into an “eager execution”-based

TensorFlow v2 (2019) & Keras (2015). Keras was developed independently by François Chollet, and like PyTorch, it was designed to be intuitive for developers to define and train their models in a modular way. Eventually, Keras merged into TensorFlow, and TensorFlow 2 was released to enable eager execution development in TensorFlow. TensorFlow 2 has a lot of design differences than PyTorch, but I find it relatively easy to use one after you’ve learned the other.

Jax (2020). Google’s latest deep learning framework that emphasizes its functional design and its just-in-time (JIT) XLA compiler for automatically fusing operations (we’ll talk about this more in the GPU section). Jax is more analogous to an amped up NumPy with autodifferentiation features, but it also has support for standard deep learning applications through subsequent libraries like Flax and Haiku. Jax has been getting more popular recently and has, in my opinion, replaced TensorFlow as Google’s primary deep learning framework. Finally, Jax has been optimized heavily for Google’s Tensor Processing Units (TPUs), i.e. anyone using cloud TPUs should be using Jax.

By this point, we’ve set the stage for deep learning to flourish — frameworks are being developed to make research on deep learning far easier, so we can now move on to talking about the types of architectures people were interested in and the core research problems of the time.

Part II.3: New deep learning architectures emerge

Here is where the focus of the field begins to diverge into applying these networks to different domains. For the sake of brevity, I am going to assume the reader is familiar with all of these works, so I will very loosely gloss over what they are. Feel free to skip this section.

Recurrent Networks (1980s - 1990s ish). Recurrent neural networks (RNNs) were popular at the nascent period of deep learning, with methods like GRU and LSTM being used in many time-series and language tasks. Their sequential nature made them hard to scale on parallel processors, making them somewhat obscure for a long time after. More recently, recurrent networks have been re-popularized in the form of state-space models (SSMs) for linear dynamical systems. Early versions of these SSMs used the linear-time-invariance (LTI) assumption to rewrite sequential computations as a convolution

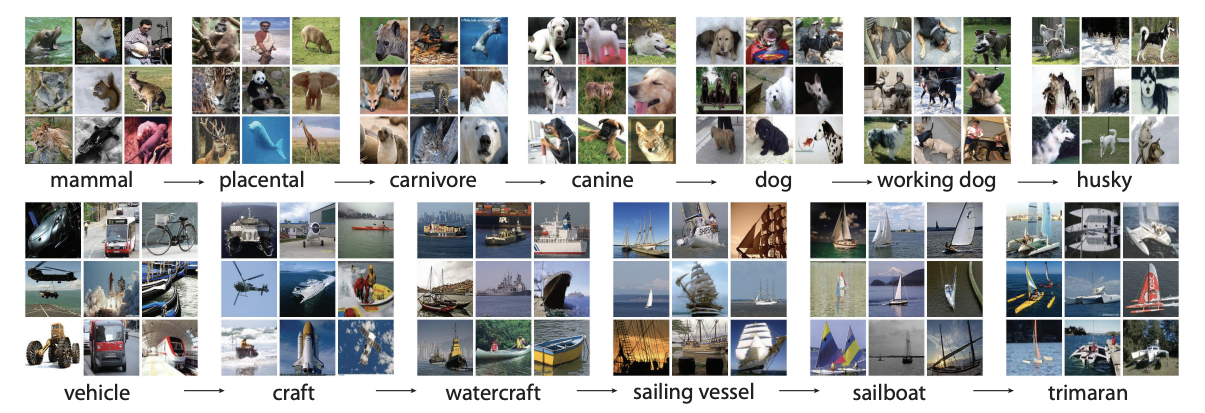

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN). CNNs were there from the beginning, and they still remain popular in the computer vision domain. The main component is the convolutional layer, which contains learnable “kernels”

Graph Neural Networks. Graph neural networks are somewhat broad, but generally involve some parameterization of a graph using standard deep learning components like a linear weight matrix. They are very hard to implement efficiently on modern hardware (think how locality would be done) and can be very large and sparse. Even though most information can be represented as a graph, in practice there are only certain settings like social media graphs in recommendation systems and biochemistry where they have seen success.

Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL). DRL generally involved approximating value functions (e.g. DQN) or policies (e.g. PPO) from the RL setting, which were traditionally represented as some kind of discrete key-value map. The standard RL setting is a Markov Decision Process (MDP) with some kind of unknown reward. DRL has also extended to post-training large language models by re-framing the alignment problem as some kind of reward maximization problem. DRL has traditionally also been hard to make efficient because 1) existing algorithms do not respond well to blind scaling, 2) agents interacting with an environment is inherently not parallelizable, 3) the environment itself is a large bottleneck.

Generative Adversarial Networks (Goodfellow et al., 2014). Also hotly contested whether these actually came out in 2014, but GANs were (a rather unstable) framework for training generative models. They had some nice theoretical guarantees (the input distribution is the optimal generator) but ultimately were hard to train, and they also were not great at high-resolution generations.

Diffusion Models (Sohl-Dickstein et al., 2015 & Song et al., 2020). I don’t have intuition as to why diffusion model generations turn out that much better than GANs, but from my own experience they definitely do. A lot of efficiency work in diffusion looks into reducing the number of noise/de-noising steps (which I find counterintuitive to how diffusion even works), and most parameterizations of diffusion models are just standard modules that are used in deep learning (e.g. MLPs, convolutions, transformers, etc.).

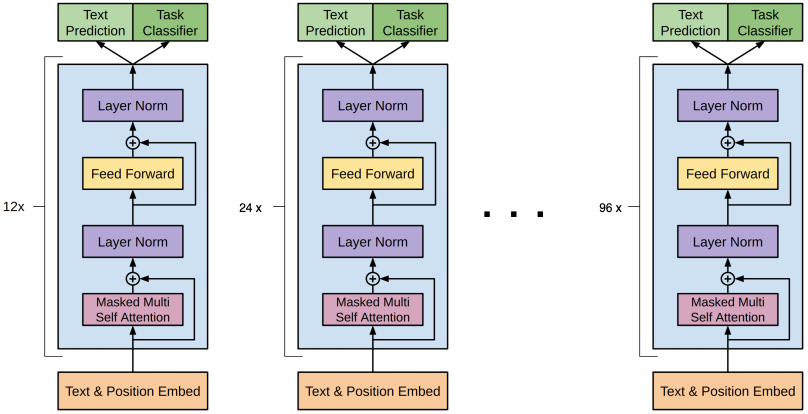

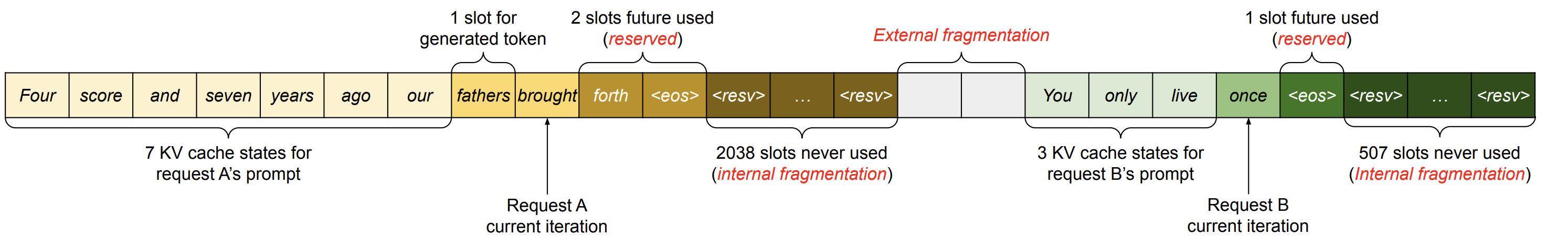

Transformers (Google, 2017). The Transformer block (and variants of it) are widely used today, and a lot of work over the past 5 years has gone into optimizing each component of the Transformer. Some of the key bottlenecks to get around are 1) the quadratic time and memory complexity of the attention mechanism w.r.t sequence length, 2) the growing KV cache that eats up on-device memory, 3) making Transformer computations faster on existing hardware. We will see a lot of these problems come up in the rest of this post.

Part II.4: Efficient convergence. Inductive biases and architectural choices

A natural question any researcher has when first exploring a domain is whether the existing mechanisms and algorithms are optimal. It was known that without tricks like dropout, regularization, the correct activation functions, learning rate scheduler, inductive biases, etc. your model would diverge or overfit on your data. It is way too difficult to pinpoint all of the architectural design changes over the years, and in, for example, the large language space, many of these changes are sort of “open secrets” — many researchers and engineers at large labs are probably aware of these tricks (e.g. local attention, RoPE embeddings, ReLU^2) but as a regular person like myself, it is hard to figure out these details from academic papers. This section will be dedicated to some cool changes that have emerged as empirically useful over the years.

II.4.a: Inductive biases that lead to better convergence behavior

There are many tricks that have been known empirically to lead to better convergence behavior for a lot of models — it is known that many older models struggled to even converge! We still don’t have a rigorous understanding for why many of these tricks are useful, but in this section we list some important architecture changes that have led to better convergence behavior. It’s not always 100% clear why these tricks work so well, so I won’t justify here.

- Dropout (p). During training, randomly mask out $p$. It is believed to be an implicit regularizer.

- Residual connections. First introduced in ResNet, add back the input to the output, effectively allowing data to skip layers.

- Scaling depth/width. For convolutional networks, EfficientNet showed scaling depth/width accordingly is useful.

- Approximating constraints. Optimization over constrained spaces can be annoying. It turns out sometimes relaxing constraints, such as birth of the reinforcement learning algorithm PPO as a relaxed and more widely-used version of TRPO.

- Cosine Learning Rate Scheduler (with Annealing). In NLP settings, the cosine learning rate scheduler (with annealing) is widely used over other fixed and decaying learning rates.

- Loss scaling. To prevent gradients from underflow or overflow (especially for quantization), a lot of optimizers have auto-tuned loss scaling enabled to normalize the gradients, then apply the inverse scaling factor.

- ReLU and variants. For a lot of tasks, especially in NLP, ReLU and its smooth variants seem to work very well as activation functions.

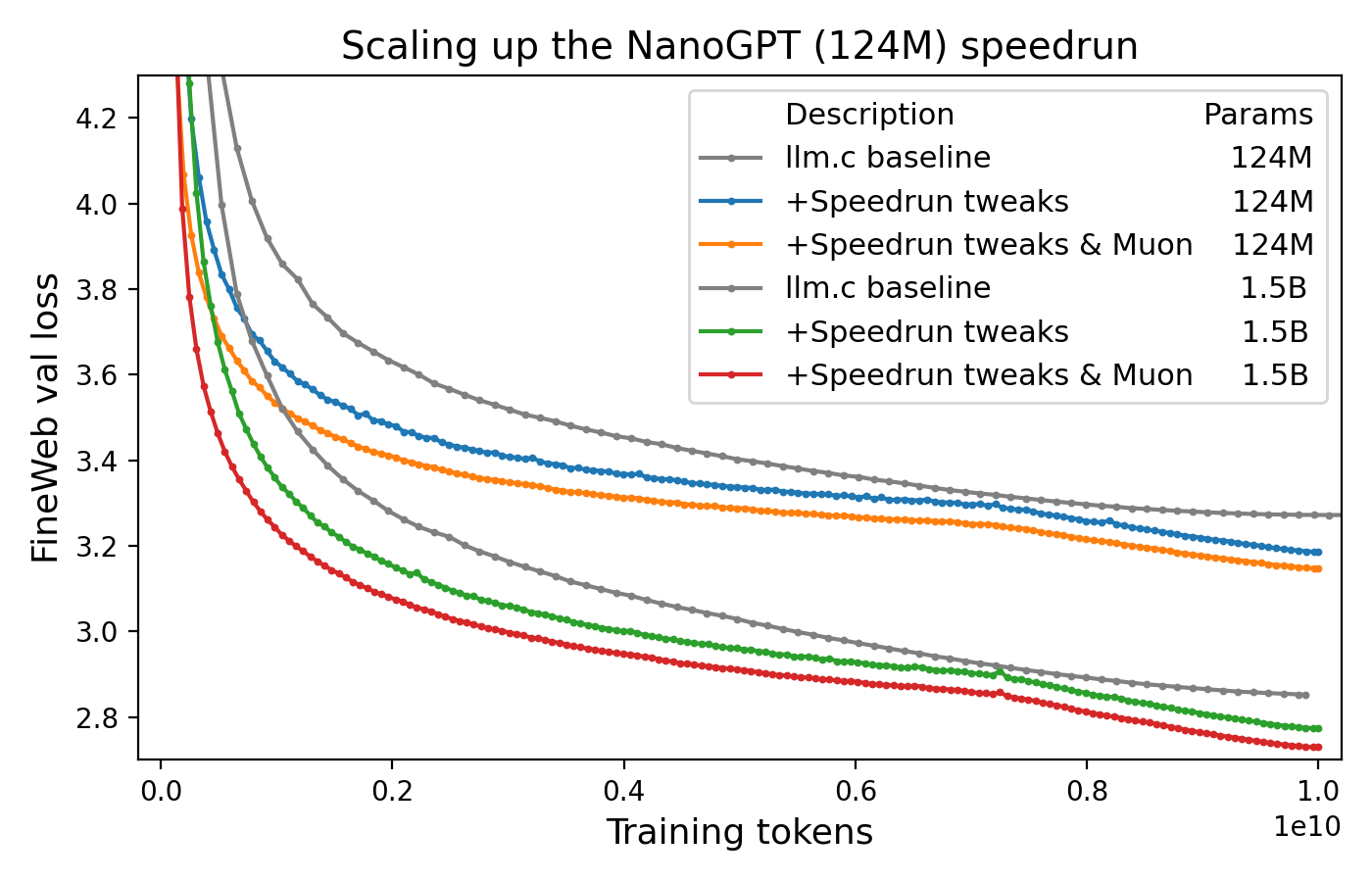

- Adam & AdamW. These momentum-based optimizers have proven to be the most impactful in deep learning despite a lot of research being done in this field.

-

Attention. The most famous deep learning mechanism today, attention seems to work very well at interactions over sequential data.

- RoPE. Rotary embeddings have similar properties to standard positional encodings, but can be written as matrix multiplications (which we love) and work better in a lot of settings.

- ALiBi. Additive attention biases have proven to work pretty well for length generalization.

- bfloat16. Low-precision training in general has shown to be practical and useful, and the bf16 datatype, which trades of precision for a wider dynamic range than fp16, has shown to be more stable in deep learning training.

- Mixture of Experts. It turns out we can keep scaling our models without all the parameters being active, and we still observe scaling laws.

II.4.b: Searching the space of solutions (meta-optimization)

A lot of traditional machine learning techniques revolve around doing some kind of grid-search and k-folds cross-validation to find the best possible model. In modern deep learning, it’s very hard to do this, especially when a single training run can cost millions of dollars. One of the more interesting spaces is neural architecture search (NAS), where we search a space of model configurations to find models that optimize some metric (e.g. performance, cost, speed) given some set of constraints. NAS isn’t really used in large model training, but it is extremely useful for trying to fit models onto low-cost devices — I’m not sure how much NAS has evolved since 2020, but I would highly recommend reading Lilian Weng’s blog on NAS!

Sakana AI’s Evolutionary Model Merge (Sakana AI, 2024). One of the newer works in NAS for language models is the evolutionary model merge algorithm, which takes components of already trained models and combines them to form various language and multi-modal foundation models. I haven’t played enough with these works to understand how effective they are, but they do demonstrate the ability to create unique models like a Japanese Math LLM with SOTA performance.

Part II.5: Efficient convergence. Optimizers

Recently, I’ve gotten the sense that optimizers are largely overlooked by many people because Adam “just works”. From the perspective of efficiency, if we can 1) compute our optimizers faster, 2) reduce the memory load of stored statistics, and 3) converge faster, then these are all wins to consider. The standard gradient descent update is written as

$$ \theta_{t+1} = \theta_{t} - \eta \nabla_{\theta} \mathcal{L}(\theta_t, x^{\mathcal{S}}, y^{\mathcal{S}}) $$

where $t$ is the iteration, $\eta$ is the learning rate, $\theta$ is the model parameters, $\mathcal{L}$ is the loss function, and $\mathcal{S}$ is the set of training values to use in the update. In standard gradient descent (GD), $\mathcal{S}$ is the entire dataset, in stochastic gradient descent (SGD) it is a randomly sampled $(x,y)$ pair, and in mini-batch gradient descent it is a randomly sampled subset. While GD has some nice and easy-to-prove theoretical guarantees

Momentum [intro]. Theoretical guarantees for SGD and GD require knowing the smoothness behavior of the loss function, which in practice is not known. In practice, SGD suffers from “steep” regions in the loss curve that cause oscillatory behavior, motivating the use of the descent trajectory as a prior to dampen oscillations. The canonical momentum update is (where $\gamma$ is a constant around $0.9$ according to (Ruder et al. 2016)). The momentum version of SGD introduces a new term that depends on the gradient:

Adam (Kingma and Ba, 2014

From a memory perspective, storing these extra statistics per parameter implies at least an extra 2x the number of model parameters has to be stored in memory during training. For large models, this extra burden is extremely problematic, as we have to figure out 1) how to fit this either into one device’s memory or multiple device’s memory, and 2) if we are using multiple devices, how to move data around effectively. Adam/AdamW is currently the standard for most large language model training as of 2024.

Preconditioning [intro]. Adam has remained the canonical optimizer for a long time, and most people are aware that it is a (stochastic) first-order optimizer. The benefit of a first-order optimizer is that they are relatively quick and only store extra statistics that is linear in the number of learnable parameters. However, it would be a more accurate estimate to use the second, third, etc. order estimates of our loss function Taylor expansion to approximate the correct update. We motivated Adam based on per-coordinate scaling factors, which is basically just applying a diagonal preconditioner to the gradient! Optimizers like Shampoo and Adagrad store preconditioners, but at varying levels of granularity (e.g. block diagonal vs. dense preconditioning matrix). On the AlgoPerf benchmark in particular, Shampoo has been shown to converge quicker than all pre-existing optimizers.

Part II.6: Pause. How much of this scale is really necessary

If you recall how std::vector<T> in the C++ standard library is implemented under the hood, you’ll remember that we have a capacity that marks allocated memory, and a true array size that is the memory that is actually being “used”. This terrible analogy was thought of at 4am just to say that as we continue to scale, a natural question is whether each parameter in the model is really that important.

II.6.a: Model Pruning

Learning both Weights and Connections for Efficient Neural Network (Song et al., 2015

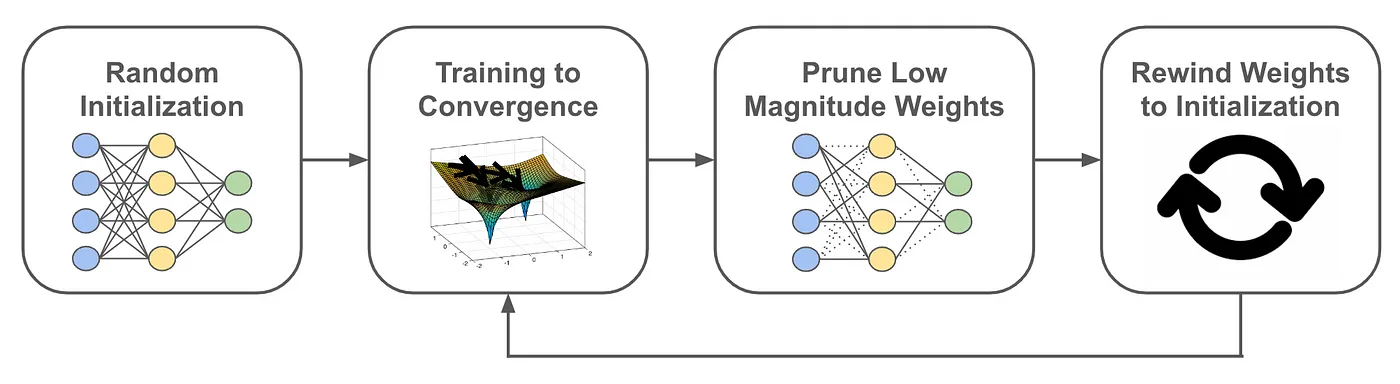

The lottery ticket hypothesis (Frankle et al., 2018

SNIP (Lee et al. 2018

$$ S(\theta_i) = \text{softmax}_{i}\left(|g_i(D, \theta)|\right) $$

This metric measures how sensitive each weight is to a loss, so they prune the smallest $S(\theta_i)$. The authors show that they can prune 99% of a network (LeNet) with a 1% increase in error.

SynFlow (Tanaka et al. 2020

$$ S(\theta) = \frac{\partial \mathcal{R}}{\partial \theta} \odot \theta $$

SynFlow was one of the first works to consider pruning from the perspective of “network flow”, as opposed just aggressively pruning weights with a low metric score. They consider scenarios where an entire layer is pruned, leading to a completely redundant network. Their experiments are mainly image models on CIFAR-10/100, but they generally showcase good performance on extreme pruning ratios (on the order of $10^{-3}$).

Are pruned models fast? From a hardware perspective, randomly pruning weights does not provide a large speed-up because operations like weight matrix multiplication rely on locality and targeting blocks of a matrix at one time. The standard implementation is to apply a $0$-mask to each pruned weight – which clearly provides no speed-ups – but clever implementations of pruning can target sparsity-aware kernels like in cuSPARSE and CUTLASS

II.6.b: Embedding Pruning or Hashing

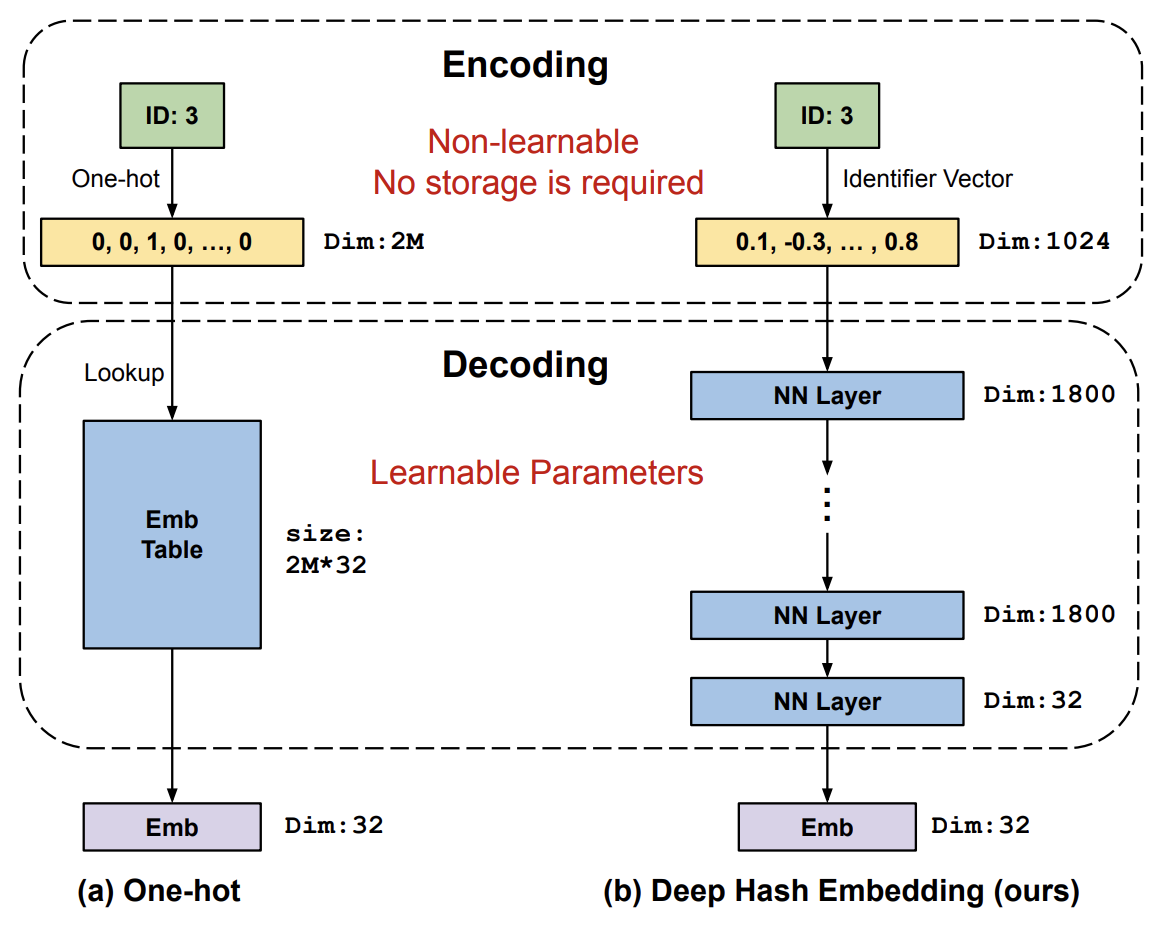

Recommendation systems is a practical field where “pruning” is somewhat applicable. In recommendation systems, users and items are typically represented as an ID that maps to a $O(10)$-dimensional embedding, meaning for social media companies like Meta and Snapchat, they will have on the order of millions or billions of embeddings in their models. For some napkin calculations, a full-precision 1B parameter embedding table with 64-dimensions each is 2 bytes * 64 * 10^9 = 128 GB for the embedding table, which is actually small in production settings! Without going into too much detail about the models themselves (for now, just abstract them as some kind of large transformer model), the embedding tables take up more than 90% of the memory load of learnable parameters.

Intuitively, under a vector space and with some assumptions about constraining the norm of each embedding, it is easy to see that we can probably cluster these embeddings in some meaningful way, and map multiple IDs to the same embedding without incurring much error. Many ideas in RecSys are not shared publicly, but common techniques like double hashing and locality-sensitive hashing are used in practice.

Learning to Embed Categorical Features without Embedding Tables for Recommendation (Kang et al. 2020

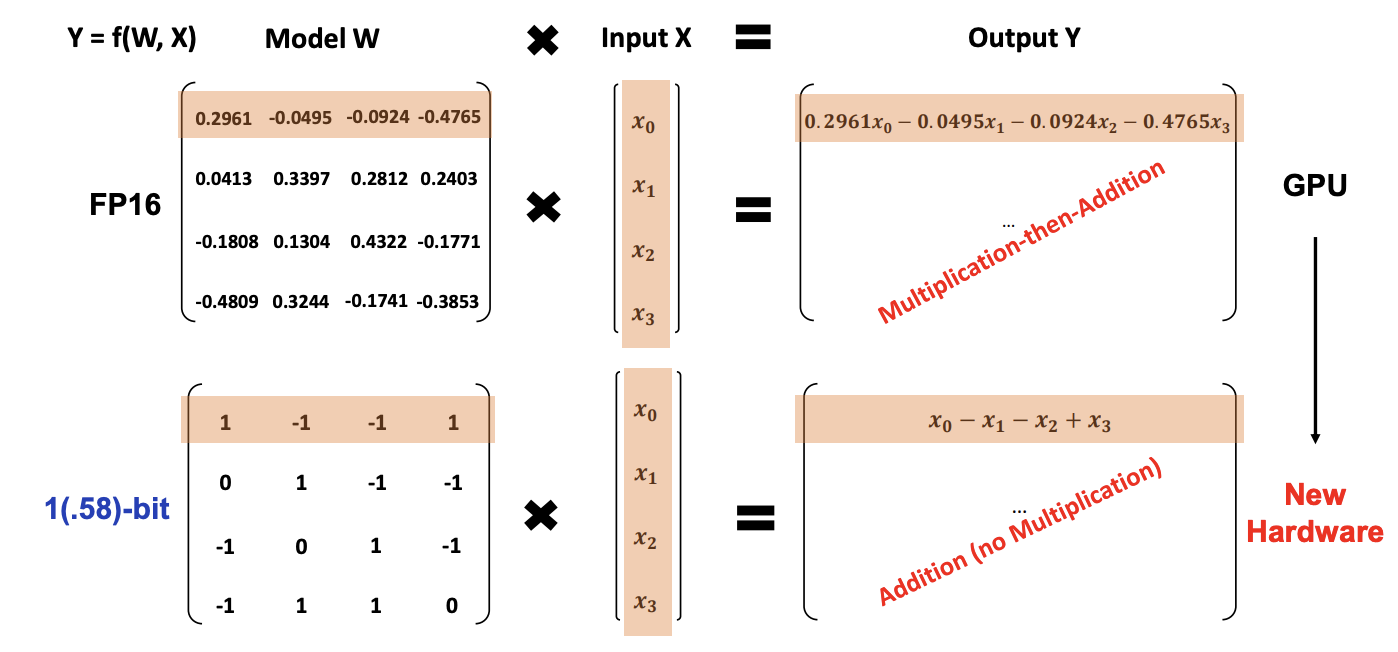

II.6.c: Quantization

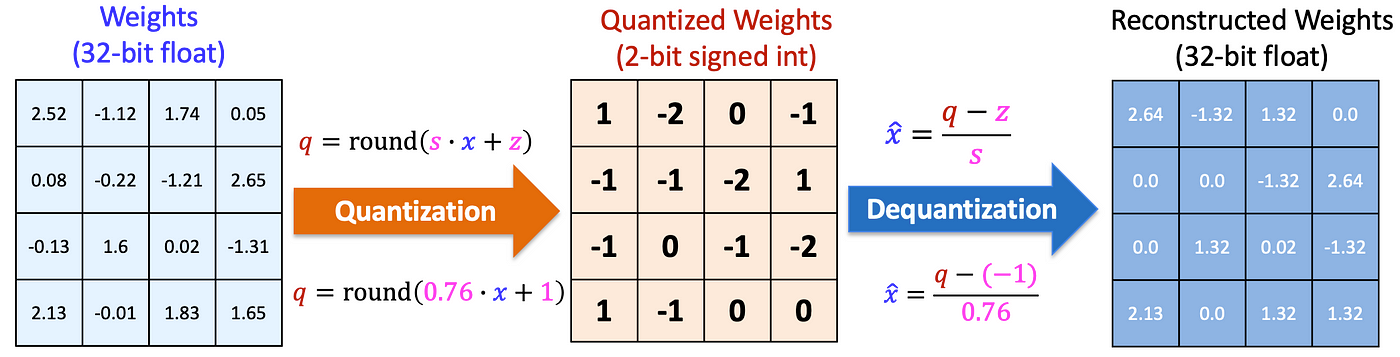

Quantization basically means instead of storing and using 32-bit floating point values (full-precision), we can use maybe 16-bit (half-precision), or 8-bit, etc. Doing so reduces the memory footprint of the model, but at the cost of precision. But there are actually many considerations, like whether you want to quantize during training or after training, whether you want to maintain model computations in a lower precision, and how to handle gradients in mixed-precision models.

The concept of quantization is not specific to deep learning and is more of a data compression problem. Generally, we are interested in reducing the memory footprint of our models — i.e. if we quantize a model with FP32 parameters to INT8

Absmax quantization to INT{b} will map to the closed interval $[- \max |X|, \max |X|]$ then evenly divide up the interval into $2^b - 1$ sections. Each value will get mapped to its closest point in the above mapping, and the quantization range is clearly symmetric.

$$ X_{int_b} = \text{round}\left(\frac{2^{b-1} - 1}{\max |X|} \cdot X\right) $$

Zero-point quantization to INT{b} instead will map to the range $[- \min |X|, \max |X|]$, but again will still uniformly divide the interval.

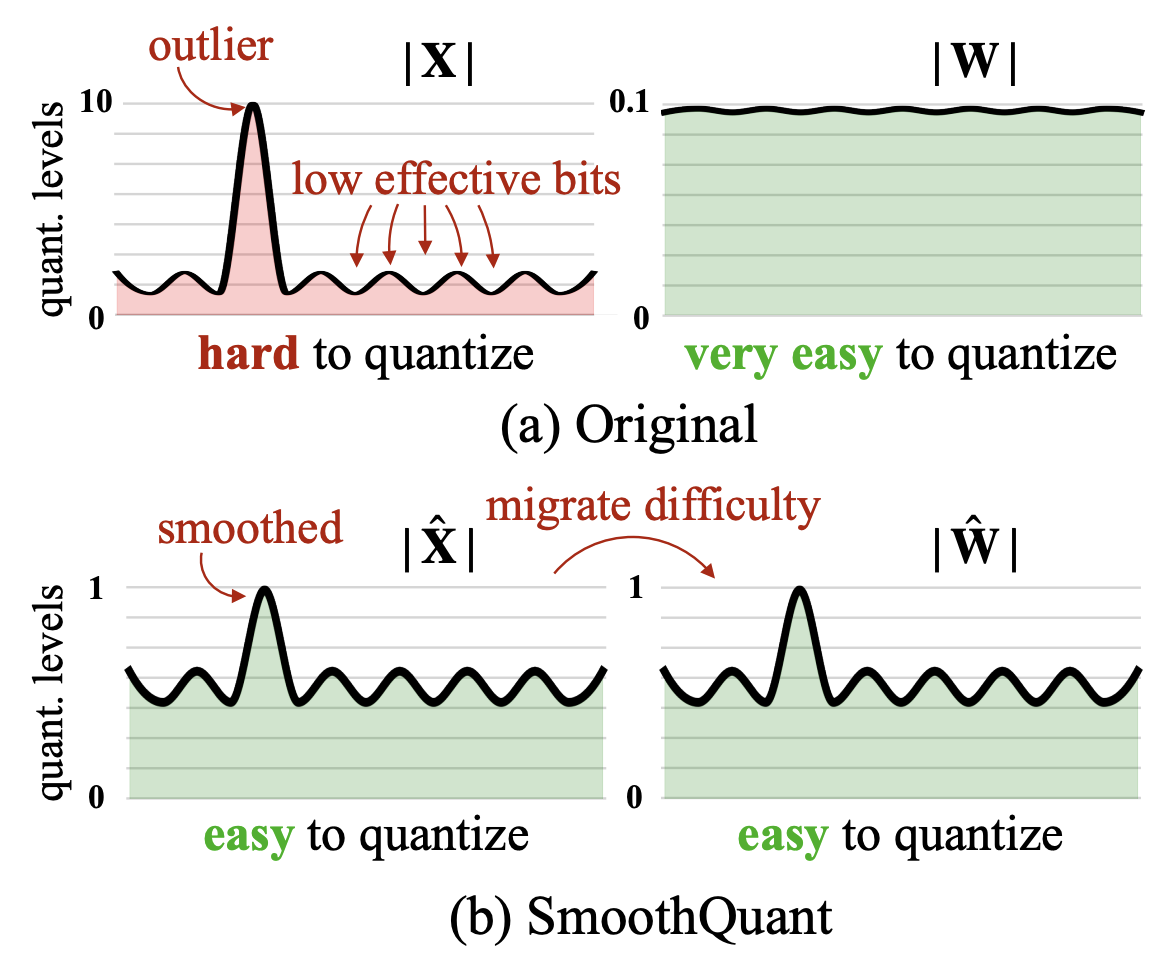

The danger of the above methods is the presence of outliers, which cause most quantization bins to be unused while increasing the quantization error. There are many other forms of quantization that do not have to be uniform in any way. Codebook quantization, for example, maps pre-defined values to a smaller set of pre-defined values, and the behavior of this map just has to be injective and well-defined

IEEE754 and floating point representations. Integers are represented with the two’s complement and are evenly spaced; however, floating point values are not evenly spaced fractions. Instead, the IEEE754 standard uses one bit to determine sign, some of the bits as exponents, and some of them as fractions (called the mantissa), giving us

$$ X_{fp32} = s^{(1)} \cdot 1.m^{(23)} \cdot 2^{b^{(8)}} $$

I’ve used the superscript to denote the number of bits used to represent that number. To clarify, the mantissa is the decimal part of the number $1.x$. In other words, in FP32, we have $23$ mantissa bits and $8$ exponent bits. However, other representations also exist to modify the representable range (increase exponent bits) or the precision (increase mantissa bits), which can be beneficial in deep learning applications.

- BF16. The IEEE754 standard for FP16 uses 5 exponent bits and 8 mantissa bits. It was discovered by the Google Brain team, however, that using 8 exponent bits, which has the same dynamic range as FP32, was more stable than FP16 due to large gradients in LLM training. Furthermore, BF16 has the benefit of being able to easily convert to and from FP32 — just chop the last 16 bits of the mantissa!

-

FP8. NVIDIA’s newest H100s have Tensor Core support for 8-bit floating points, which are represented as either E5M2 or E4M3

E5M2 meaning 5 exponent bits and 2 mantissa bits, and E4M3 meaning 4 exponent bits and 2 mantissa bits. Notice that with 8 bits, we can never do the FP32 → BF16 trick, but we can go from FP16 to E5M2. . We will talk more about Tensor Cores soon.

Automatic Mixed-Precision training (2018). In 2018, NVIDIA released the Apex extension to PyTorch, which introduced automatic mixed-precision (AMP) training on CUDA devices. The core idea is that lower precision BLAS operations are significantly faster with the introduction of hardware units like NVIDIA Tensor Cores, but not all operations (e.g. logarithms, trig functions) are safe to downcast due to their sensitivity to dynamic ranges / precision. Under the hood, torch.amp has a list of “safe” operations that are downcast to FP16/BF16 to provide essentially free speed-ups to the programmer. In most modern training schemes, you should be using AMP unless you want full control over your model operations.

II.6.d: The Grandfather of Efficient ML and TinyML

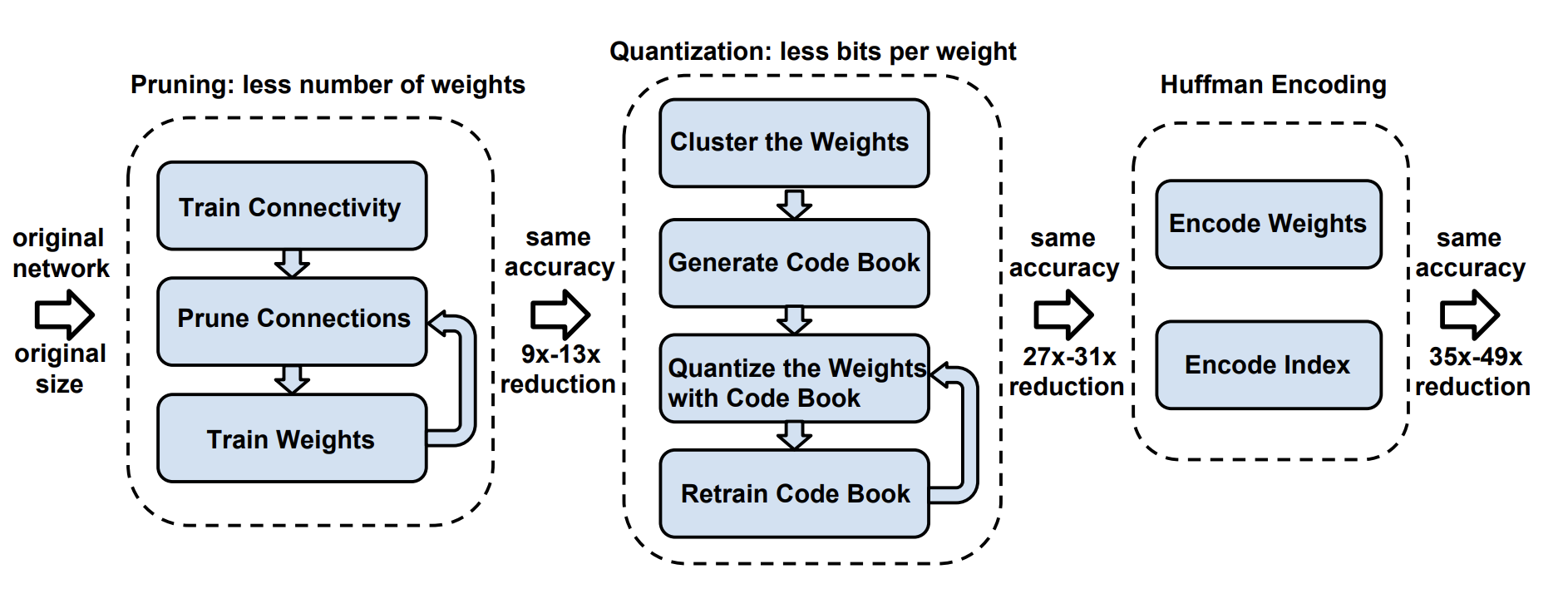

Deep Compression: Compressing Deep Neural Networks with Pruning, Trained Quantization, and Huffman Coding (Han et al. 2015

Part II.x: Hardware

If you don’t know anything about a GPU except that it’s really good at parallel workloads, this section is a gold mine of information! I think this section motivates a lot of the future work very well, especially as we begin to consider hardware-aware algorithms for scaling our models. Otherwise, I would skip ahead to Chapter III.

You’ve probably noticed that up until this point, a lot of the aforementioned works were interested in improving and tweaking architectural components for the sake of better convergence behavior and ease of scaling. If your model doesn’t fit on a single GPU, find a way to divvy it up on multiple GPUs — we can sort of ignore optimizing for memory accesses, node-to-node latency, and other systems-y lingo because at this scale, it’s probably fast enough

II.x.1: NVIDIA GPUs from Tesla (2006) to Ampere (2020)

Let’s continue where we left off. A lot of this section will appear kind of hand-wavy, but don’t worry — it makes a lot of sense to just assume things are a certain way before digging into why. If you ever become interested in the why, you’ll have to start reading denser sources of information. I recommend the PPMP textbook and the GPU MODE Discord!

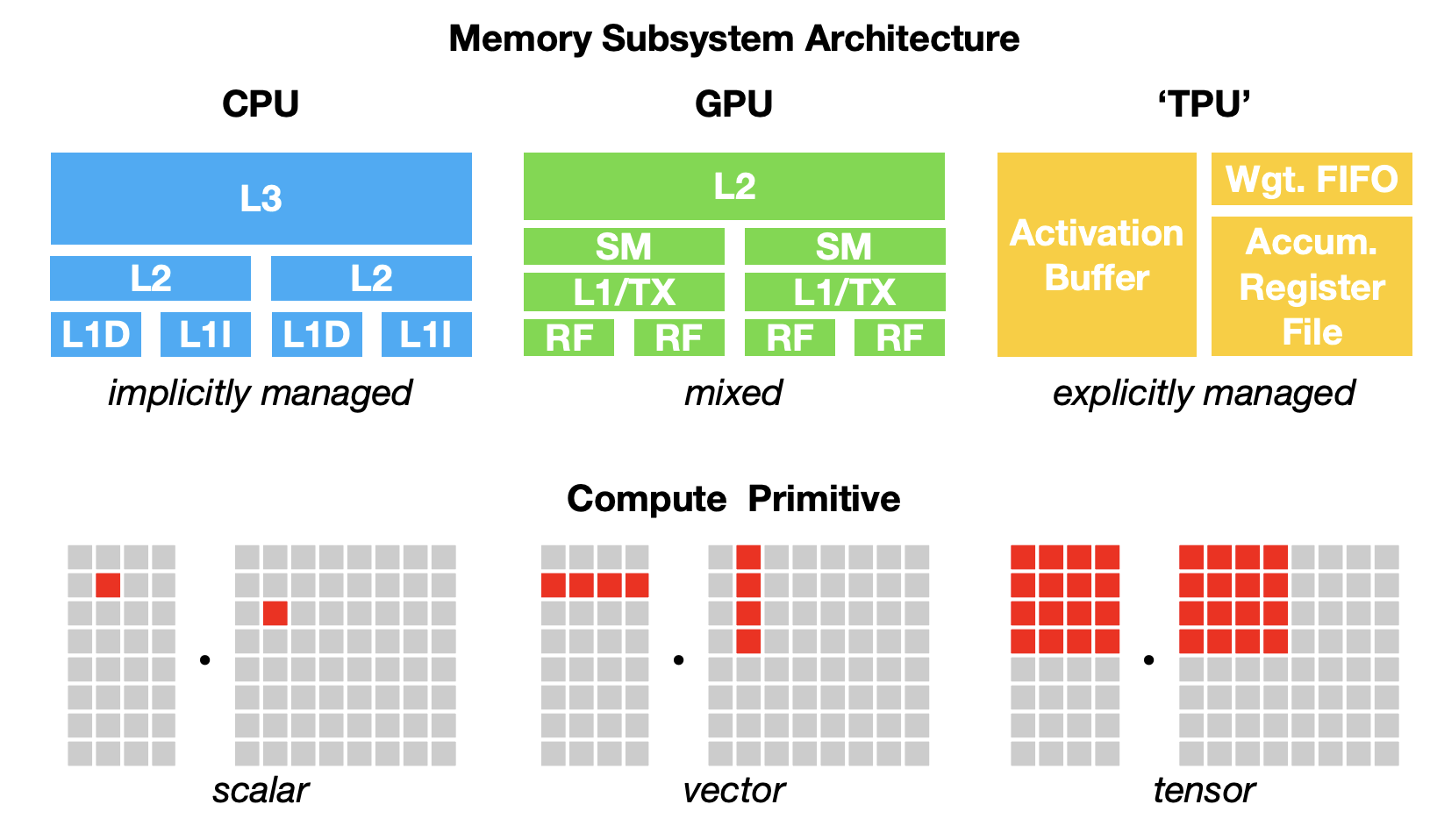

Compute Structure. Let’s first talk about why GPUs are so good at parallelized computations. CPUs were designed to handle very complicated logic like branching (think if-else operations), and a large portion of the processor die is dedicated to this. NVIDIA GPUs instead trade off this chip space for more cores and specific hardware units that can perform instructions like small matrix multiplications in very few cycles. It’s like having 100 automatic sewing robots (GPU) vs. a human (CPU). Sure, the human being is smarter and more flexible/capable for general tasks, but if the task is to maximize production of clothes, it is much more useful to have the sewing robots. Starting from the Tesla series GPUs, NVIDIA used many CUDA cores with the SIMT (single-instruction, multiple threads) abstraction, so effectively a GPU really was just a bunch of small processors running in parallel. To understand how this abstraction works together with actual workloads, however, we need to understand how data is moved from the memory to the actual processors.

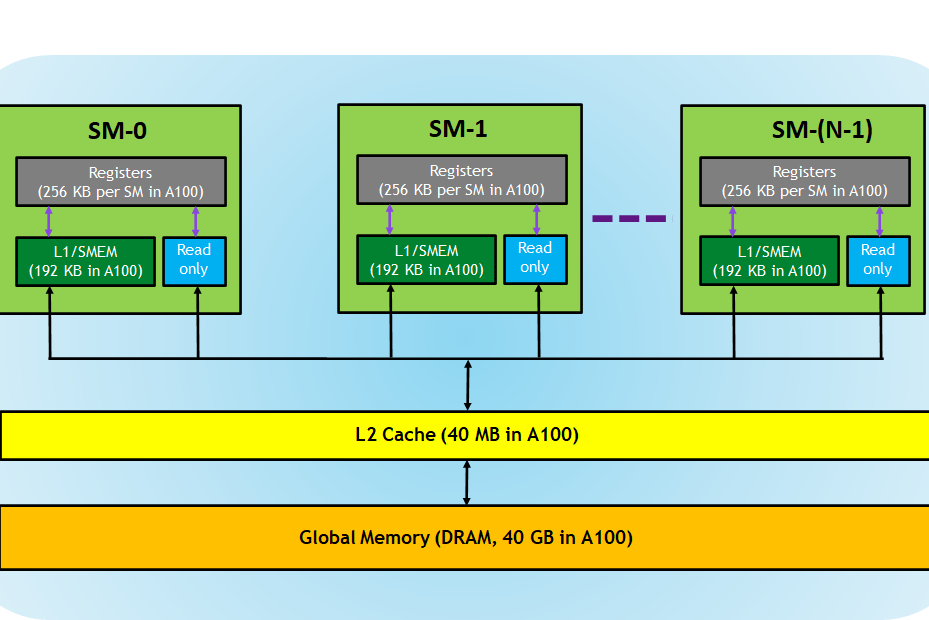

Hierarchical Memory Structure. The above is an extremely simplified view of how compute and memory are divided in a GPU starting from the Tesla architecture. Let’s assume that performing some kind of memory access from global memory (DRAM) is slow. This design emphasizes data reuse to minimize access to global memory. From Figure 12, we can also observe that different hierarchies of memory are shared across different abstractions (e.g. L2 cache is shared among SMs, but L1 cache is per SM), which is extremely important for optimization.

-

SMs (streaming multiprocessors) are the individual units that run their own processes

This is not entirely true. SMs actually have their own CUDA cores / streaming processors that get assigned the relevant work, but for our abstraction it suffices not to think about them. , and you generally have on the order of $O(100)$ of these. For now, assume that they can run many threads (up to 1024) at the same time.- Each SM has its own registers (256K per SM on an A100), which are the fastest form of memory to access and write to.

- L1 and L2 caches are a form of fast (roughly 10x faster than DRAM) but small memory — just assume for now that they are a limited but extremely valuable resource.

- DRAM (dynamic random access memory) is the main working memory on a GPU. When you hear the term “A100 40GB”, it means that you are dealing with an A100 GPU with 40GB of DRAM. It is also often labelled as “high-bandwidth memory” (HBM).

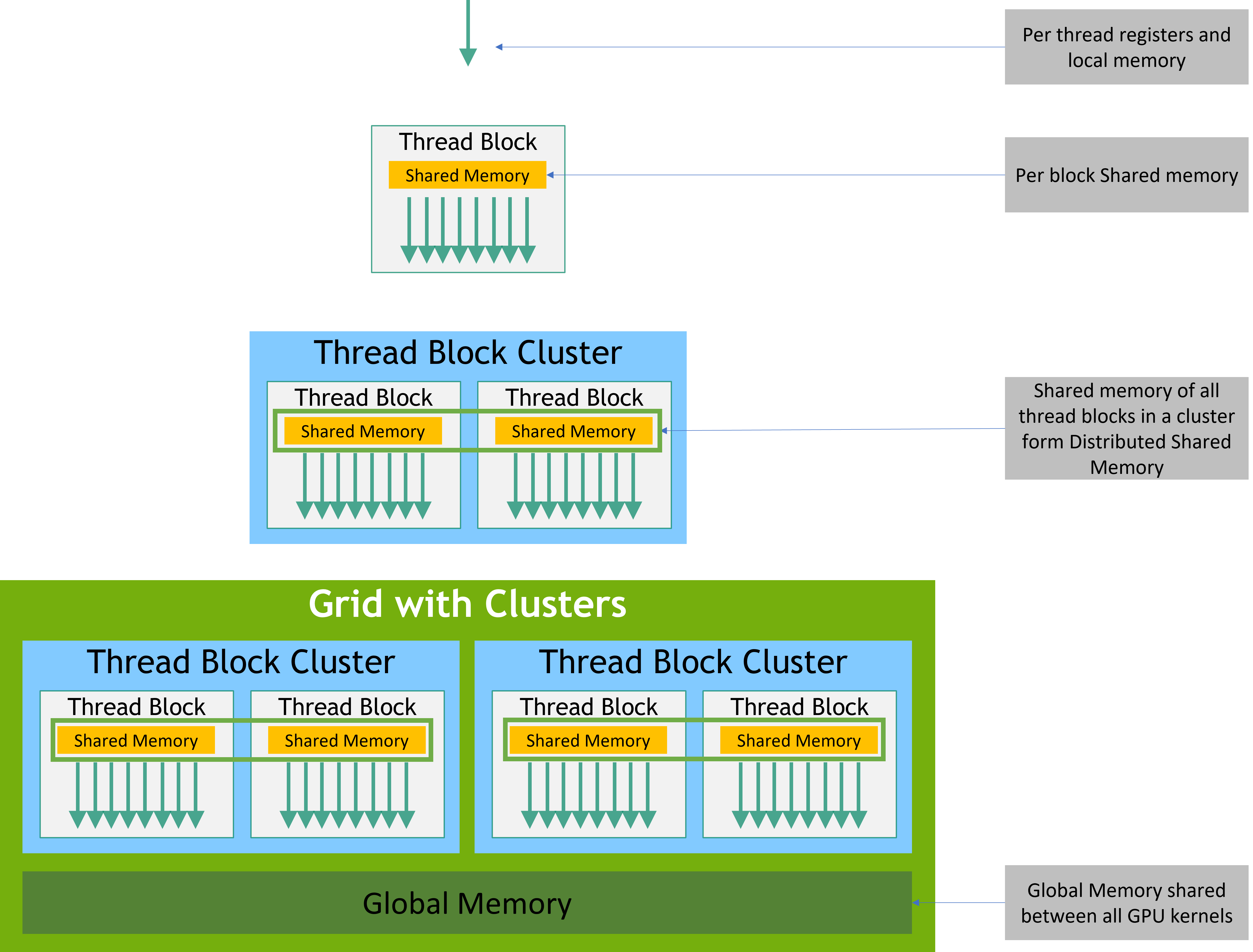

Streaming Multiprocessors (SMs), Thread Blocks, Warps. The CUDA programming model is a bit convoluted at first glance, and it’s hard to motivate the design choices without understanding the hardware. Generally, the most important thing to understand is that:

- Kernel/device functions operate at the thread-level, so we have to specify per-thread behavior in our device functions. Variables defined are implicitly accessed through registers.

- We mentioned earlier that CUDA is SIMT — groups of threads called warps share the same instruction over different data (typically 32 threads per warp). Starting from the Volta architecture, threads actually have their own program counter and call stack and can call different instructions.

- Kernels are launched in “grids” of “thread blocks”; threads/warps in the same block can access shared fast SRAM memory, which is useful for communicating between threads in operations like stencils / convolutions.

- Each grid is independent (and run in parallel), and generally cannot communicate. For example, it is often convenient to launch an independent grid for each batch in the forward pass of a network.

- We usually launch kernels from the CPU/host. In PyTorch, it is implicit when we define our model code; in CUDA, it is using the triple bracket notation:

f<<<<a,b>>>>(**kwargs), whereais the number of grids, andbis the number of thread blocks per grid. The hardware is responsible for scheduling these threads on the relevant devices to maximize device usage, or “occupancy”.

An example template of launching a CUDA kernel from the host is below.

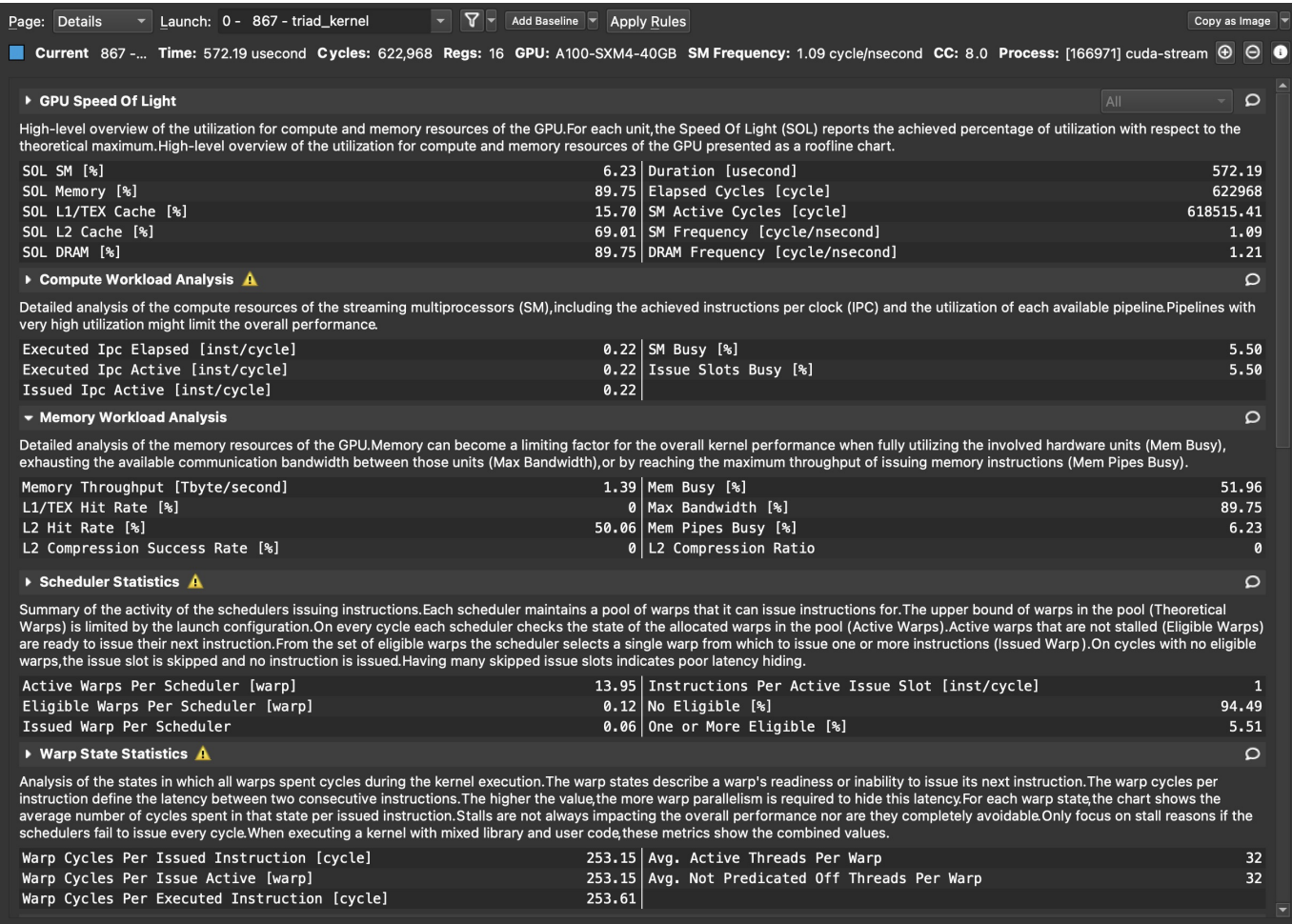

Compute-bound vs. Memory-bound workloads. In parallel GPU workloads, we are concerned with bottlenecks that limit the throughput of the entire workload. At a high-level, this can either be due to our cores being fed lots of operations, or due to blocking operations from data movement in memory. In most language-based deep learning applications, the latter occurs, and we call these programs “memory-bound”. Note that being compute-bound on an A100 does not imply that you will reach the ~300 TFLOPS advertised by the A100 — certain compute operations like activation functions are slower, as we will soon see. We often estimate these bottlenecks by computing the arithmetic intensity, which is the number of compute operations divided by the bytes accessed in memory. Finally, the CUDA ecosystem features a variety of profilers for developers to use to understand their programs, which we list in the Resources section.

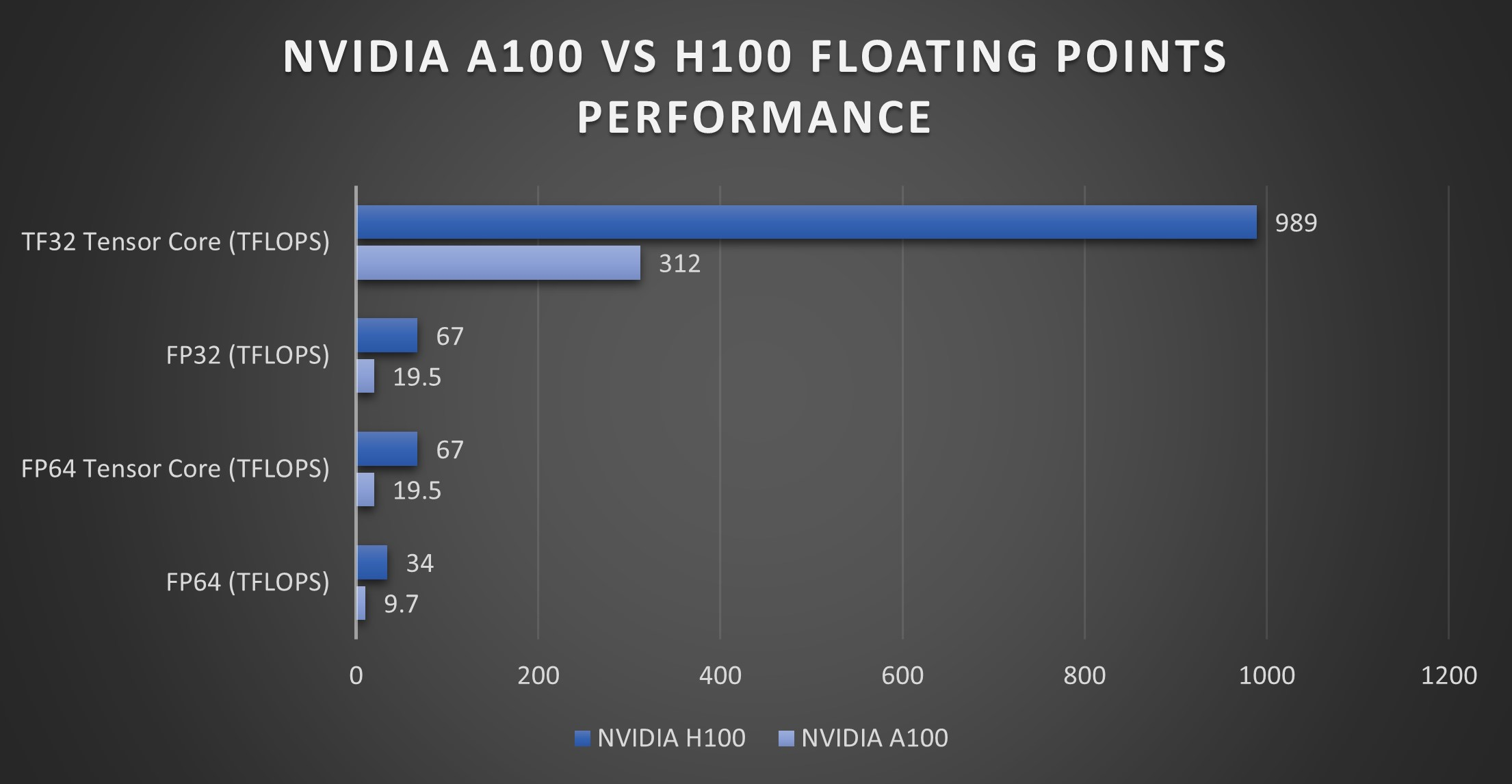

GPUs on Steroids: Tensor Cores (2017). If there was any concern about whether vectorized CPU operations could compete with GPUs, you can throw that all out the window due to the introduction of Tensor Cores with the release of the Volta microarchitecture in 2017. Tensor cores are specialized hardware units for performing 4x4 floating point matrix multiplications extremely fast

Certain smaller precision data types like FP16 and FP8 are faster on later editions of Tensor Cores. . Because matrix multiplication can be re-written as block matrix multiplication and deep learning consists of a small set of operations, Tensor Cores are extremely useful, and optimizing throughput often comes down to sufficiently feeding the Tensor Cores. See Figure 14 for a comparison of Tensor Core speed on A100/H100 GPUs.

Intra-Device Bandwidth: PCIe vs. SXM & NVLink. When dealing with larger workloads, another bottleneck to consider is device-device and host-device communication bottlenecks. The standard interface is Peripheral Component Interconnect Express (PCIe), which can be used to connect devices to other devices or to the host. PCIe lanes connect your devices, and a larger number of lines provides more (potential) throughput for data movement. Starting from the Pascal microarchitecture, NVIDIA also began selling GPUs with the SXM form factor, which basically means they have specific ports for SXM interconnects and are connected on a specific SXM board (it still communicates to the CPU through PCIe). The SXM GPUs can also use NVLink, which is a special protocol for larger memory bandwidth. Generally, unless you are dealing with huge workloads, the type of intra-device communication will not even be the bottleneck you are looking for. For example, the H100 PCIe device-to-device bandwidth is 2 TB/s, while the H100 SXM5 device-to-device bandwidth is 3.35 TB/s.

Other relevant optimization details you can just assume exist. Understanding how to use these often involves profiling kernels and balancing the limited amount of “fast” memory we have. Many of these optimizations are highlighted in this amazing article on optimizing matrix multiplication in raw CUDA: https://siboehm.com/articles/22/CUDA-MMM. Because our GPU compilers aren’t unbeatable, it is useful to know many of the following details:

-

Shared memory: I didn’t mention this explicitly in the memory hierarchy above, but shared memory

Not to be confused with OS shared memory. The naming here is kind of confusing I’ll admit… is SRAM that is shared between all threads in a thread block. Many tricks involve using shared memory accesses over HBM accesses. - Thread coarsening: There is overhead for launching threads (it’s not free!) so sometimes it’s actually better to perform sequential operations on the same thread.

- Memory coalescing: When we access HBM/DRAM, it is faster to access them in “bursts”, or contiguous chunks. In other words, we like structured accesses.

- Constant memory: A small, global read-only memory that is useful when we have to re-use the same data a lot.

- Pinned memory: When transferring between CPU RAM and GPU DRAM, NVIDIA GPUs have a Direct Memory Access (DMA) unit that handles the memory transfer to free up compute. Because the DMA uses physical addresses, the OS paging system can accidentally cause the DMA to transfer the wrong CPU memory — pinned memory is a primitive to ensure a chunk of memory will not be paged out, giving up speed-ups on this transfer.

- Streams: We can avoid “waiting” sequentially for independent blocking operations by telling the device to put them on different streams, so it is safe to run them concurrently.

Parallel patterns. It is also important to understand what types of operations are known to be parallelizable. In deep learning, we understand that matrix multiplications (matmuls) are extremely efficient, but many other operations are also parallelizable and have well-known design patterns:

- All BLAS operations

- Convolutions

- Stencil operations

- Reductions (e.g.

torch.sum()) - Radix Sort

- Merge (e.g. Kogge-Stone and Brent-Kung, useful for state-space models)

- Histograms

A comparison of notable GPU specs over the years. We’ll be using PCIe and not SXM numbers for reference here.

| GPU | $\mu$-arch | Year Introduced | Peak Theoretical TFLOPS | Peak Theoretical Bandwidth (GB/s) | Notable inclusion. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GTX 580 3GB | Fermi | 2010 | 1.58 | 192 | Used to train AlexNet (2x). |

| Tesla P100 16GB | Pascal | 2016 | 21.2 | 732 | First datacenter GPU. |

| V100 16GB | Volta | 2017 | 28.3 (FP16) | 897 | Introduced Tensor Cores. |

| RTX 3090 24GB | Ampere | 2020 | 35.6 | 936 | Popular consumer GPU for deep learning with a lot of VRAM. |

| A100 80GB | Ampere | 2020 | 312 | 1935 | Huge DRAM pool and very popular choice for clusters. |

| H100 80GB | Hopper | 2022 | 1600 (FP8) | 2040 | Introduced new components like the TMA for accelerating LLM inference and training. |

Energy costs. The power consumption of these devices is pretty important to know if you are using your own machines / clusters. I don’t have a strong intuition for these numbers, but generally they float around the $O(100)$ watts range for current high-end GPUs. For example, the A100 80GB consumes 250W when fully utilized, so it would come out to 600 kWh a day, which is roughly 40 USD in electricity bills if you live in the US. Tim Dettmers has a useful blog that explains these power considerations when building your own machine.

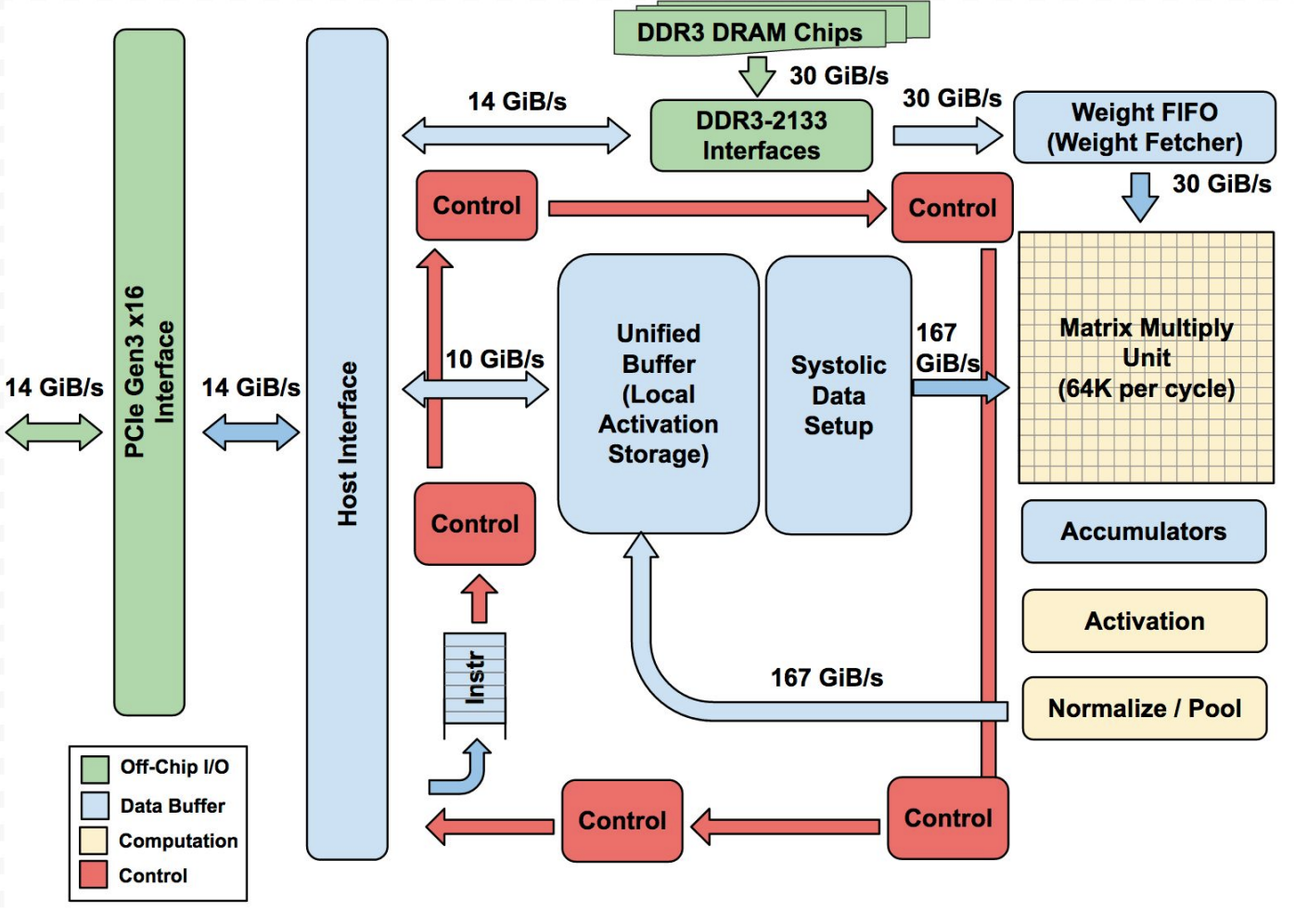

II.x.2: Google’s Tensor Processing Units (TPUs)

The CUDA ecosystem is not the only choice for parallel processing. Google’s in-house Tensor Processing Units (TPUs), first introduced publicly in 2016, are a custom application-specific integrated circuit (ASIC) designed for deep learning workloads at Google. TensorFlow and Jax have dedicated compilers for TPUs, making them the standard choice for programming these devices (PyTorch support has been added, but it’s not great).

- While NVIDIA and AMD GPUs have features like the texture cache that are designed for gaming applications, TPUs specialize in high-throughput, low-precision matrix multiplication with low energy usage.

- TPUs use their own systolic array “Tensor Core”, which handles 128x128 multiply-accumulate operations (compared to the 4x4 for NVIDIA!) in a single instruction cycle. This design favors large matrix computations.

- The TPU features special instructions and hardware for activation functions and a super-fast buffer for moving data.

- Google has since come out 6 generations of TPUs, with the latest using 256x256 Tensor Cores to accelerate even larger model computations.

- You can’t actually buy your own TPUs, and you have to use cloud-provided TPUs (or work at Google) to use them for your own applications.

- Similar to the design of SXM boards for NVIDIA GPUs, TPUs also have dedicated “TPU Pods” to connect multiple devices with high-speed communication.

II.x.3: Potpourri of other interesting hardware

The popularity of NVIDIA GPUs is in part due to the success of the Transformer and other parallelizable architectures. However, for different memory access patterns, there exist other hardware alternatives that could later play a pivotal role in the field.

Field-gate Programmable Arrays (FPGA). FPGAs have seen some use in efficient deep learning as a low-cost hardware to target. Because of the availability of GPUs and ASICs like TPUs, it is hard to justify designing and programming these devices for actual workloads. Nevertheless, I wouldn’t write off FPGAs — they have a variety of use-cases in the sciences and low-latency applications, and there is a chance that they will become important in deep learning as well.

Neuromorphic Chips. We know that the human brain is extraordinarily efficient and powerful (except maybe mine), so a natural question is whether we can design computer hardware around the brain. There are some primitives like Spiking Neural Networks that have been designed in the past, but most of this work has not really taken off in “modern deep learning”. There are also some small neuromorphic chips like IBM’s TrueNorth, but I haven’t seen significant progress in this area yet. Like quantum computers, however, I am hopeful that people crack this research direction and apply them to AI!

Etched (2024) [site]. Very recently, a startup company came out with a Transformer-specific ASIC called Sohu that they claim accelerates Transformer workloads (not sure if it’s also training?) by an undefined margin. Little information is known about the underlying hardware and how good it actually is, but a Transformer-specific ASIC itself is not a far-fetched idea.

Part III: The Era of Scale till we Fail (2020-Now)

GPT-3 (OpenAI, 2020

Its successor, GPT-3.5 / ChatGPT would later blow up the field of AI to the public, but these methods would introduce a combination of new post-training tricks (instruction-tuning & RLHF) and better data that are not rigorously understood. Scaling these models became a whole new game than all previous works, with the goal of building general-purpose “foundation models” that could be applied to any task. For this reason, the rest of this post will primarily focus on transformer-based architectures or recent alternatives (e.g. state-space models, Kolmogorov-Arnold Networks). Many of the following ideas certainly apply to existing deep learning methods, and molding these approaches to older algorithms is definitely a useful research direction that may yield meaningful results.

Part III.0: Let’s talk about the H100 GPU

NVIDIA’s Hopwell microarchitecture (2022), along with the H100/H200 GPUs, introduced a few notable new features to accelerate deep learning workloads. In addition to having effectively more/faster memory, higher memory bandwidth, and more CUDA & Tensor Cores than the A100, the H100 also features:

- Tensor Memory Accelerator (TMA). The whole concept behind “streams” that we introduced before was to ensure non-overlapping operations like memory movement and using the Tensor Cores were done in parallel. The TMA is a new hardware unit that asynchronously computes memory addresses (this is not a free operation on older devices and had to be done with registers!) for fetching data between shared memory and global memory. In other words, we no longer need to dedicate threads to perform data transfers and can instead focus on feeding the Tensor Cores.

- High-speed low-precision. Tensor Cores now support the FP8 data type and can theoretically reach 3300 TFLOPS for FP8 operations.

- Thread block clusters. A new level of the CUDA programming hierarchy sits above the thread block — all threads in a thread block cluster are concurrently scheduled onto SMs, making communicating between them more efficient with the CUDA cooperative_groups API.

- SM-to-SM shared memory. They formally call this distributed shared memory, but basically a programmer can now access shared memory that sits on other SMs (presumably through a shared virtual address space) without having to move it to the L2 cache / global memory.

- DPX instructions. The promotional material for these instructions keeps claiming that they “accelerate dynamic programming (DP) algorithms”, but I’m pretty sure from the Hopper guide that it’s just specialized instructions for min/max and additions that are common in DP algorithms — the actual loop and sequential nature of DP isn’t changed at all.

With the release of the H100, a few interesting developments have been made to target these devices, including FlashAttention3, which we will talk about in the coming section.

WGMMA (Warpgroup Matrix-multiply-accumulate)wgmma.mma_async instruction allows threads to launch matrix multiplication on the Tensor Cores as a non-blocking operation. In other words, they’re free to handle other tasks like data loading to further increase throughput and hide latency.

ThunderKittens (Spector et al., 2024). The H100 has a lot of new features that are really annoying to target yourself. ThunderKittens is a domain-specific language (just an extension on top of CUDA C++ basically) that you can use to abstract away a lot of these features at the warp-level while the compiler handles all of the nitty-gritty details. I haven’t tried it myself because I don’t have an H100, but it looks like a promising library to consider using. I also included the blog in this section because it has some nice details about how they target the H100 that are really well-written!

Part III.1: The Era of Scale (on a single GPU)

By this point, there were clear signs that scaling up the number of parameters in a model and the amount of data was almost purely beneficial for improving model capabilities. The obvious solution to scaling networks was to 1) add more compute and 2) wait for longer training runs. But adding devices is extremely expensive and does not linearly add more memory and training speed as we will discuss in Part III.2, so there was a lot of interest in squeezing out as many FLOPS and bytes out of every GPU as possible. Before it was settled that the attention mechanism was extremely important as is, alternatives with better runtime and memory scaling were first proposed.

III.1.0: Early insights

Activation checkpointing (Chen et al., 2016

KV Caching (2017?).

III.1.a: Shaving complexity through Approximate Methods

A long series of works have proposed approximations to the general attention mechanism in hopes of scaling these methods to sub-quadratic memory and runtime. We list some notable examples in chronological order

-

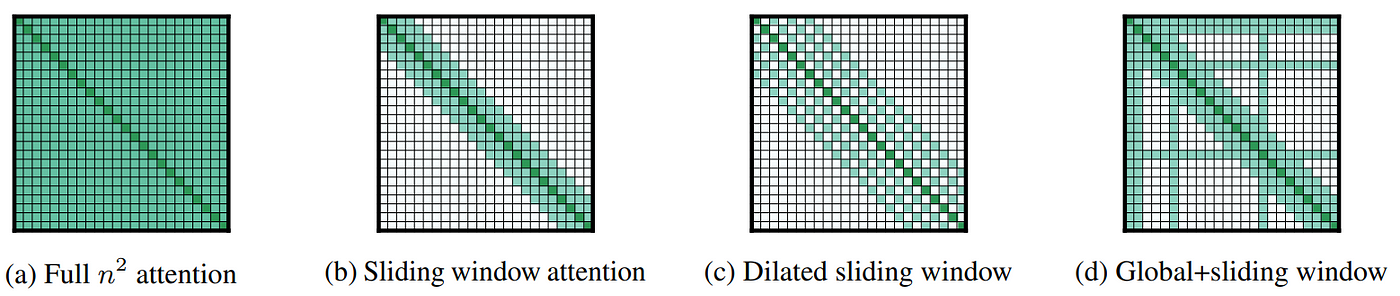

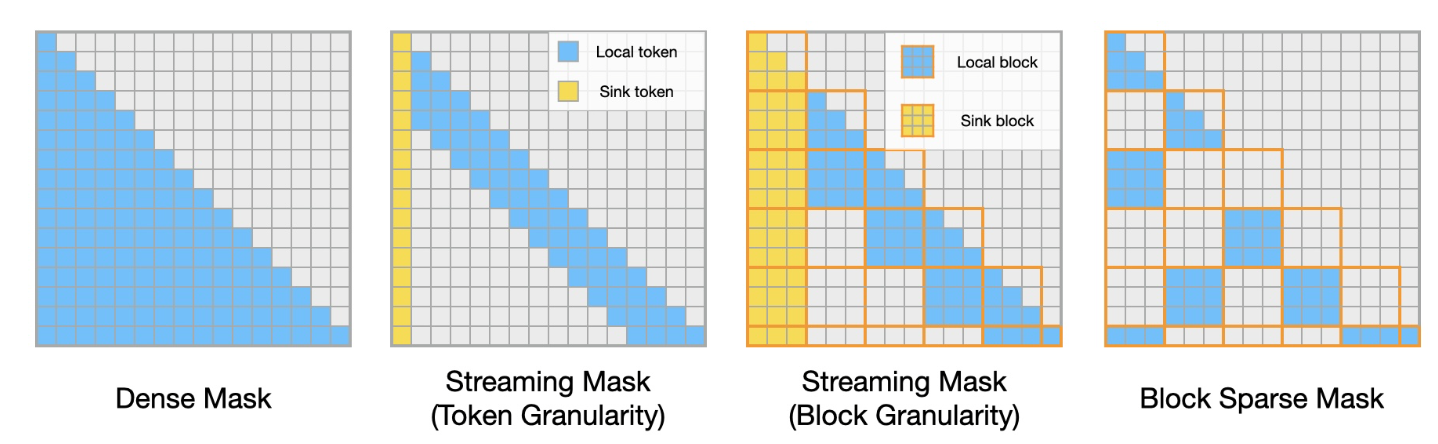

Sparse Transformers (Child et al., 2019

) [Paper] [Code]. Early work on constraining fixed sparse attention patterns (across heads, though this isn’t too relevant anymore) so each query can only attend to $O(\sqrt{N})$ of the keys. They evaluate on a variety of image and audio tasks, although the results aren’t high quality for today’s standards. -

Reformer (Kitaev et al., 2020

) [Paper] [Unofficial Code] This idea is really cute — they posit that attention weights are largely concentrated on a few elements, so they use a locality-sensitive hashing scheme find the $K=\log(N)$ nearest keys for each query and only compute those for the attention mechanism. -

Linformer (Wang et al., 2020

) [Paper] [Unofficial Code]. They reason using the Johnson-Lindenstrauss lemma There are many variants, but the core idea is that we can (randomly) project points in a high-dimensional normed space to a lower-dimensional normed space such that distances are preserved up to some error that is a function of the number of points in the space. Basically, it’s used a lot whenever we want to analyze whether moving to lower dimensions is “fine”. that when computing the attention matrix, they actually just compute it as a product of two low-rank matrices. Their proposed decomposition is extremely simple, and it literally is just projecting down the key and value matrices to a constant dimension. -

Longformer (Beltagy et al. 2020

) [Paper] [Code]. Longformer is just an empirically-motivated set of masking patterns over the attention matrix for efficiency. They mainly use a sliding window local attention scheme (see Figure 17), but also allow attending sparsely to global positions. -

Performer (Choromanski et al., 2021

) [Paper] [Unofficial Code]. Instead of using a low-rank or sparsity assumption, they observe that the attention operation $A(i,j) = \exp(q_i, k_j^T) = K(q_i, k_i)$ is a kernel, which can be written in the form $\phi(q_i)^T \phi(k_i)$. The choice of $\phi$ is motivated to be an unbiased estimator using random features See https://gregorygundersen.com/blog/2019/12/23/random-fourier-features/ for background. , and ultimately the decomposition removes the annoying softmax function and reduces the number of operations. -

InfiniAttention (Munkhdalai et al. 2024

) [Paper] [Unofficial Code]. InfiniAttention avoids sequence-length time/memory complexity by storing a recurrent-style attention matrix that is fixed size, but is updated in memory. They chunk up sequences and sequentially process them, theoretically enabling infinite scaling at the cost of a fixed representation.

While many tricks like sparsity, low-rankness, and kernel decomposition were tried, in the end, most of these methods are unused in modern LLMs. Some of the more practical approximations for the attention mechanism are a lot simpler in practice and provide clear memory or runtime improvements over the original.

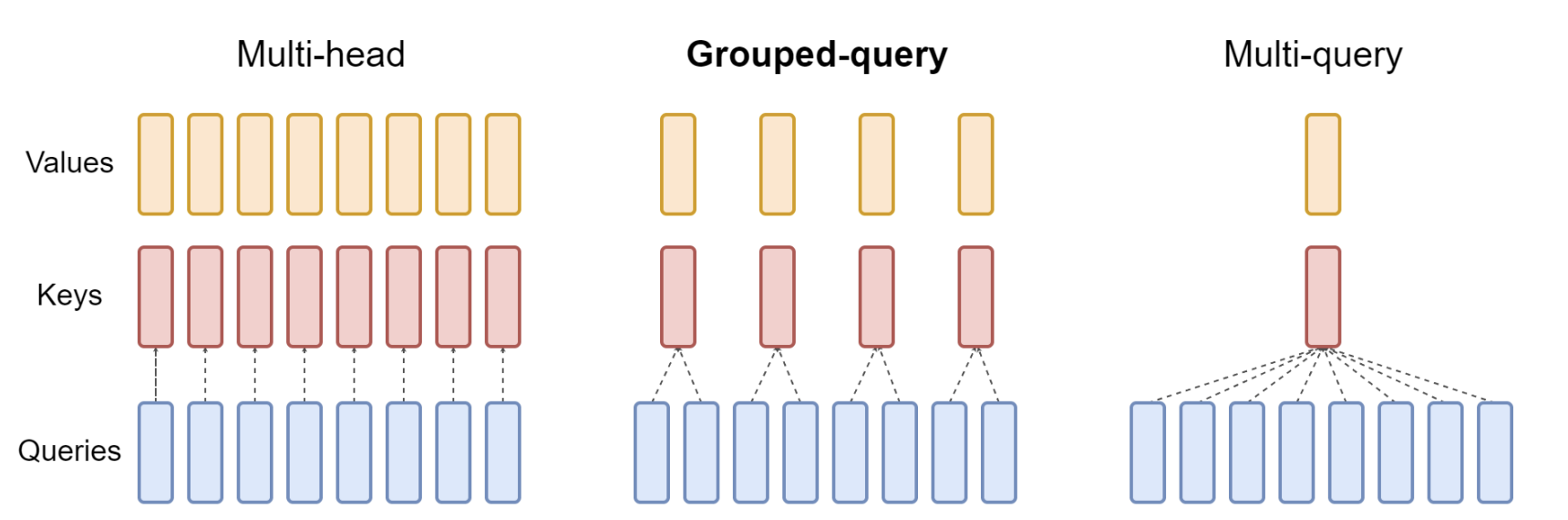

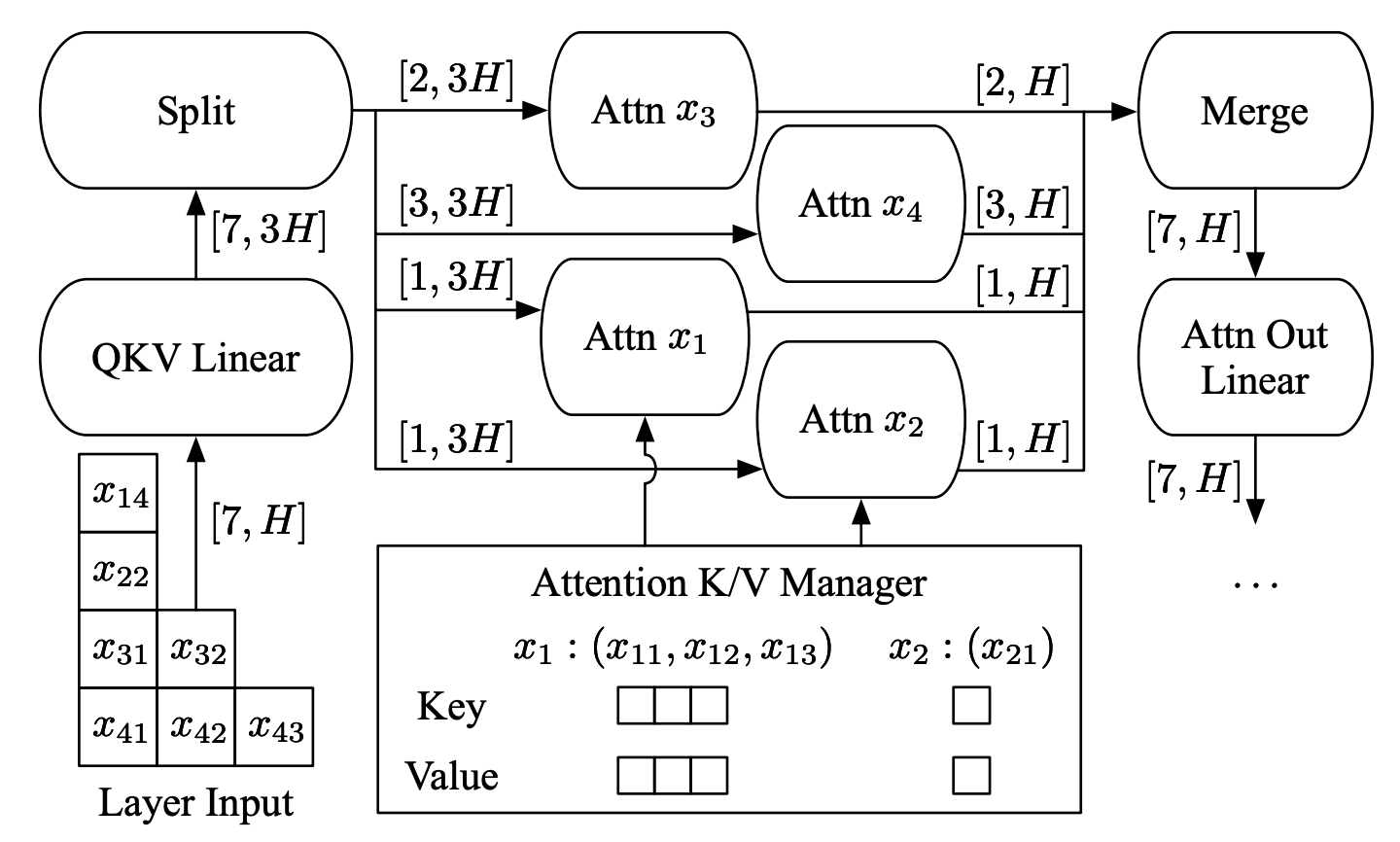

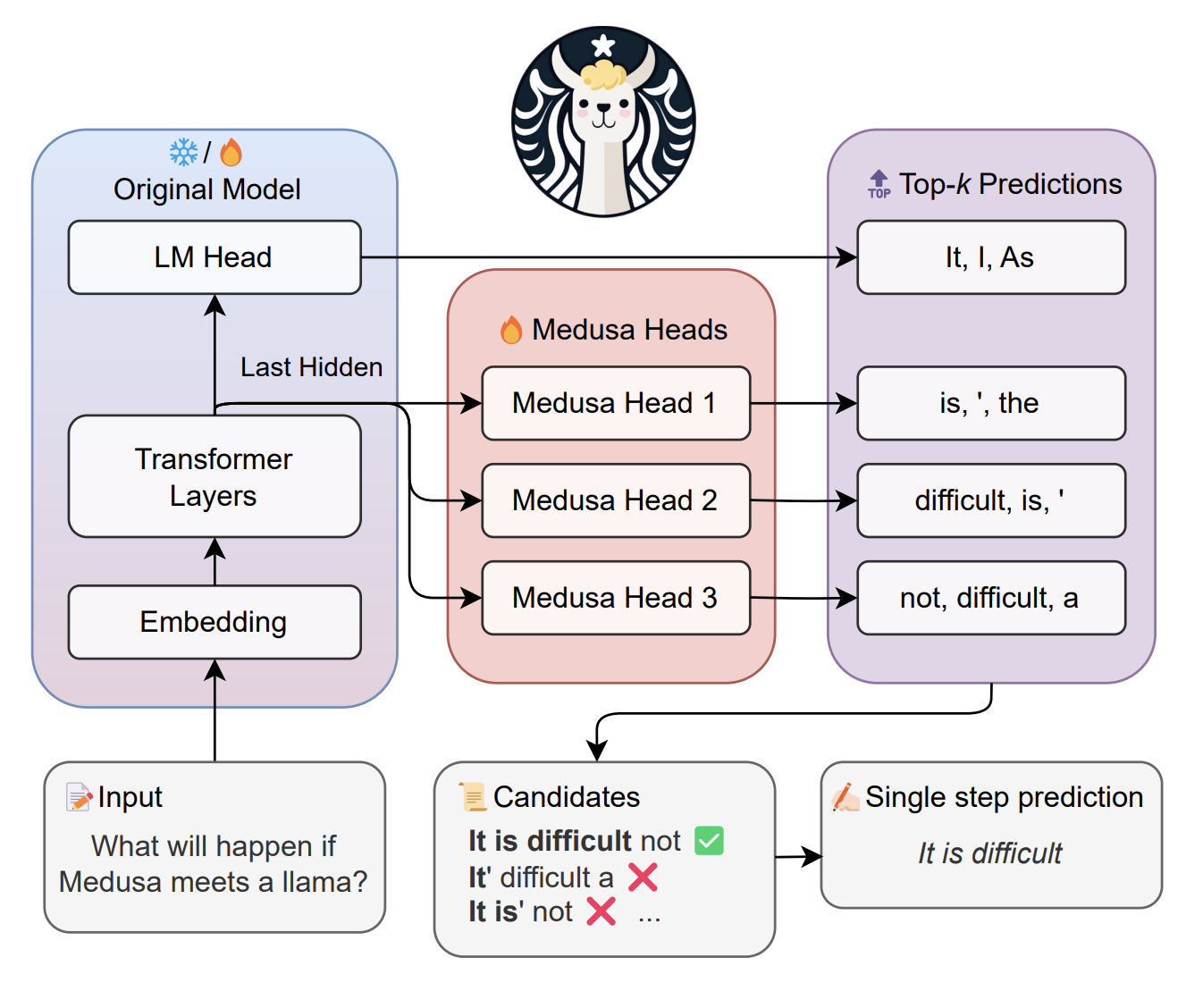

Grouped Query Attention (Ainslie et al., 2023

III.1.b: Architecture Design

Some architecture choices have been motivated by existing bottlenecks in scaling large models. For language models, the naive approach is to just increase the number of attention blocks, but there are other methods that balance memory and capacity tradeoffs differently.

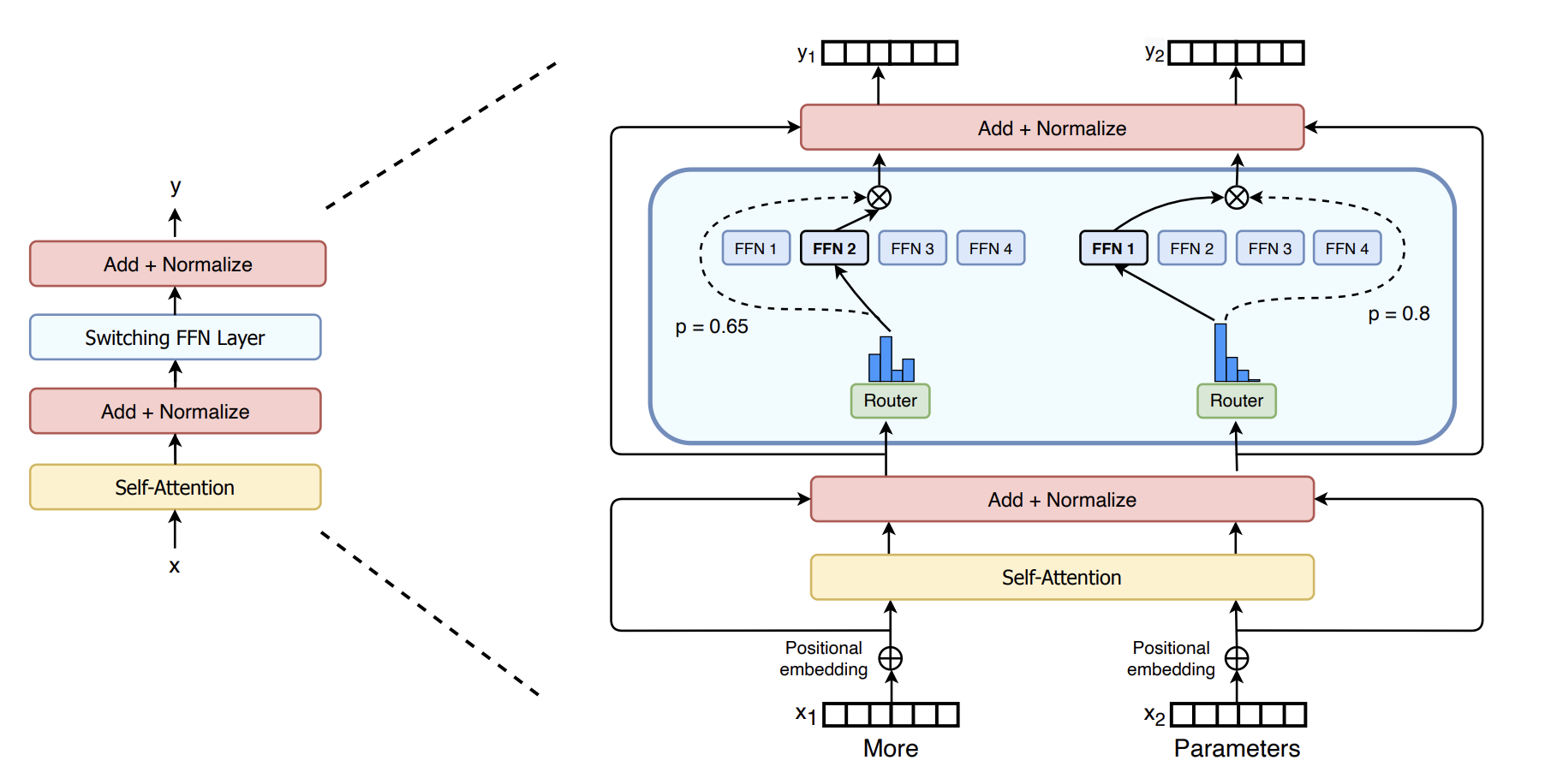

Mixture-of-Experts in NLP (Shazeer et al. 2017

Primer: Searching for Efficient Transformers for Language Modeling (So et al., 2021

Switch Transformers (Fedus et al., 2021

III.1.c: Fine-tuning Large Models Efficiently

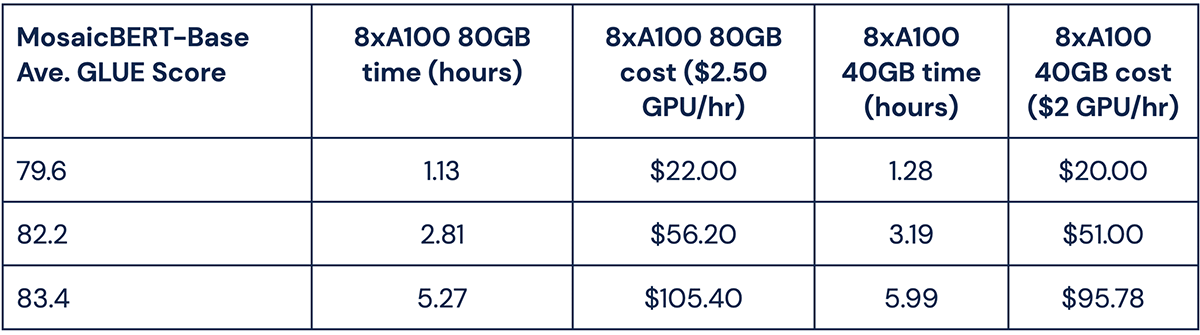

It is well known that pre-training large foundation models is way out of the budget of a standard researcher

Adapters (Houlsby, 2019

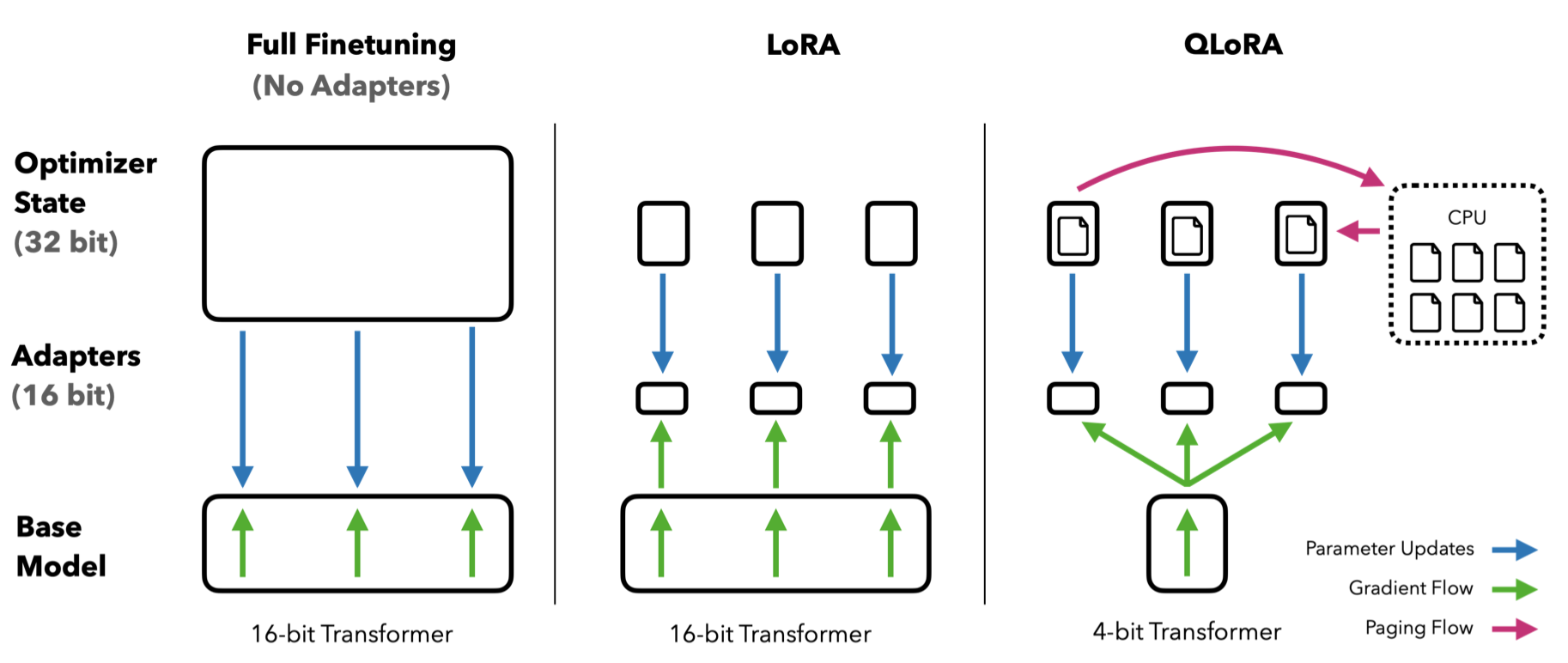

LoRA (Hu et al., 2021

Q-LoRA (Dettmers et al., 2023

- To solve (1), they introduce the 4-bit NormalFloat type, which quantizes the weights by evenly dividing the range based on the Gaussian measure.

- To solve (2), they introduced a paged optimizer based on NVIDIA unified memory to move optimizer states between GPU DRAM and CPU RAM when necessary, as they are only used for backpropagation.

- To solve (3), they quantize the quantization constants to a lower precision. Q-LoRA is basically a whole collection of memory reduction techniques for performing LLM fine-tuning on affordable hardware. The LoRA component remains untouched, but the memory reductions allow LoRA to be applied to all layers in a model for better performance.

Combined together, a Q-LoRA tuned layer can be written as:

$$ f(X^{(bf16)}) = X^{(bf16)}\text{dequant}(W^{(NF4)}) + X^{(bf16)}A^{(bf16)}B^{(bf16)} $$

Huggingface PEFT Library. There are a few other major parameter-efficient fine-tuning (PEFT) works like LoRA and adaptors such as prefix tuning, soft prompts, and $(IA)^3$ that all kind of boil down to “I believe that we can fine-tune a model by slightly adding or injecting information to the pre-trained model”. Honestly, PEFT as a whole is extremely hand-wavy, and a lot of the methods are ways to condition or perturb model weights based on the fine-tuning dataset. HuggingFace has a nice wrapper for running different PEFT methods for your models. For details on specific PEFT variants, I’d suggest reading this survey paper.

Remark. I couldn’t really fit this work in, but I wanted to mention ReFT, which I think is a really cute idea that turns out to work well in practice. Based on the hypothesis that high-level concepts in language model are directions in some representation space, they fine-tune model generations by learning disjoint “interventions” over the model hidden states (i.e. an adapter motivated by interpretability work). I haven’t fully read into the interpretability work that led to DII, but their experiments are pretty convincing.

III.1.d: Fused kernels and the GPGPU

Read Part II.x: Hardware before continuing in this section.

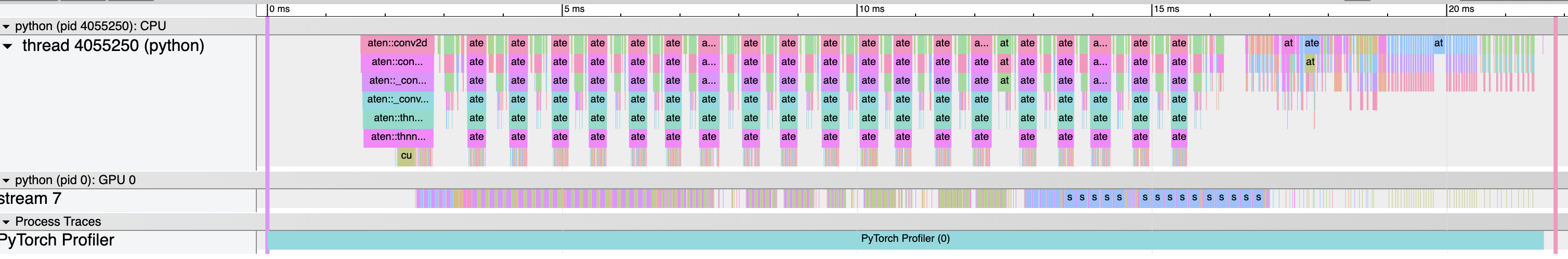

Eventually, it became clear that cute tricks like sparsity and dimensionality reduction on the attention mechanism were not only hurting model performance, but they weren’t even providing wall-clock speed improvements to these models. You may have heard the term “fused kernel” used to describe an optimization to a deep learning model. The term kernel is overloaded quite often, but in this instance it just refers to a program run on the GPU. We focused a lot in the earlier sections on building up models as modular, stackable components that we could freely optimize, but allowing this flexibility is not necessarily hardware-friendly. Consider the following example for computing the attention operation in PyTorch:

$$ \mathbf{O} = \text{softmax}\left( \frac{\mathbf{Q} \mathbf{K}^T}{\sqrt{d_k}} \right) \mathbf{V} $$

In eager execution mode or without a clever compiler, every assignment $y = f(x_1,x_2,…)$ in the code above will do something like this.

- The variable(s) $x_1,x_2,…$ will be sitting in the GPU DRAM/HBM. We first have to load it onto the processors/SMs, which is quite slow.

- We perform the transform $f(x_1,x_2,…)$ on device. This operation is relatively fast because the torch functions (e.g.

torch.matmul) are heavily optimized. - We store the result $f(x_1,x_2,…)$ which sits on device registers back into DRAM, and point to it with the variable $y$.

- If $y$ is ever used in subsequent lines, we have to load it back into registers, and repeat.

Fused kernel implementations usually aim to remove these intermediate stores and loads to DRAM that Python compilers cannot optimize out. Depending on the level of granularity in the language used (e.g. Triton vs. CUDA), we can control data movement at all levels of the GPU memory hierarchy. To get a sense for the relative speeds of each level of the hierarchy, we list some data movement speeds on an NVIDIA H100 GPU found in this microbenchmarking work. For reference, the H100 runs at roughly 1.5 GHz, or $1.5 \times 10^9$ clock cycles per second.

| Type of Memory Access | Number of Clock Cycles |

|---|---|

| HBM Access | ~480 clock cycles |

| L2 Cache Hit | ~260 clock cycles |

| L1 Cache Hit | ~40 clock cycles |

| Shared Memory Access | ~30 clock cycles |

| Register Access | ~1 clock cycles |

In the following section, we’ll talk a bit about existing fused kernel strategies for attention, followed by some examples in other fields.

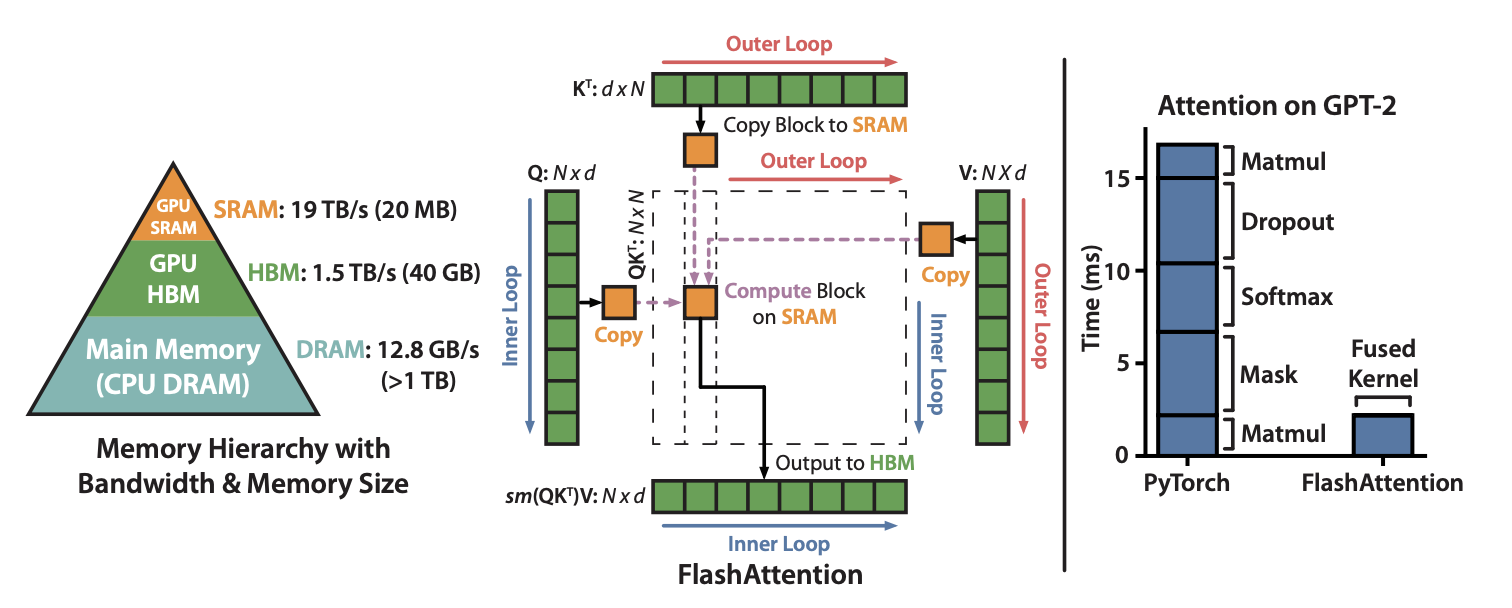

FlashAttention (Dao et al., 2022

FlashAttention2 (Dao, 2023

FlashAttention3 (Shah et al., 2024

xFormers (Facebook Research, 2021) [Repo]. The xFormers repository features a series of CUDA and Triton kernels for various Transformer components like attention, layer norms, dropout, etc. Prior to the release of FlexAttention, the xFormers repo was also the standard for a fast attention algorithm with custom attention biases.

Liger Kernel (Hsu et al., 2024

Other examples. While fused kernels have seen extensive interest in transformer-based LLM applications, there are other areas where fused kernels were critical to their success. We list a few notable examples below.

-

FlashFFTConv (Fu et al. 2023

). It is well known that for functions $u(x), v(x)$ with Fourier transforms $\mathcal{F}(u), \mathcal{F}(v)$, the convolution can be written as $ \{u * v \} (x) = \mathcal{F}^{-1} \{\mathcal{F}(u) \cdot \mathcal{F}(v) \} $. It is also well known that the Fast Fourier Transform can be computed in $O(N \log N)$, so we can compute convolutions for state-space models in $O(N \log N)$ where $N$ is the sequence length! However, despite the better runtime complexity than attention, in practice, Transformers are still faster to train on modern hardware. FlashFFTConv re-writes the FFT into a different decomposition that contains matrix multiplications to take advantage of Tensor Cores. -

Mamba: Linear-Time Sequence Modeling with Selective State Spaces (Gu et al., 2023

). Prior state-space model methods (e.g. S4) impose a linear-time-invariant (LTI) constraint on the state update matrices so they can be re-written as a convolution to avoid the sequential computation needed for recurrent algorithms. While these models were interesting at the time, Mamba was a huge deal in the community because it removed the LTI constraint and added an input-dependent selection mechanism for its parameters. To remove the LTI constraint, the authors wrote a kernel to keep the recurrent state in fast shared memory to keep the computation fast. -

InstantNGP (Müller et al. 2022

). The novel view synthesis problem The novel view synthesis problem is generating unseen views of a scene given a few reference images. With a fine granularity, you can even produce entire videos or interactable scenes from just an image. has mostly been solved using Neural Radiance Fields (NeRFs), but the computational bottleneck of increasing resolution was large. InstantNGP was a hashing scheme for position-dependent features that was entirely written as a fused kernel, and is widely used as a standard in many subsequent NeRF works as well. -

MSA Pair Weighted Averaging for AlphaFold3 (Me!). AlphaFold3 is a closed-source scientific breakthrough (most notably winning the 2024 Nobel Prize in Chemistry!) developed by Google DeepMind for predicting generic molecule interactions. While they most likely developed the model in Jax and optimized it for their in-house TPUs, researchers and start-ups outside of Google are interested in using the model for their own biotech use-cases. Ligo Biosciences is a start-up developing an open-source version of this model, but certain algorithms such as the Triangular Multiplicative Update and the MSA Pair Weighted Averaging algorithm have extreme memory bottlenecks when written naively in PyTorch. I was interested in was writing fast and readable kernels for these algorithms (both forward and backwards passes), which I wrote in Triton

Triton is a programming language (it’s more of a library for Python) that compiles to an intermediate representation (IR) that NVIDIA GPUs can use. Rather than abstract at the thread-level like we’ve discussed for CUDA, it instead operates at the thread block level, and is far easier to prototype with. We will talk about this later, but torch.jit() compiles to Triton code. . The MSA Pair Weighted Averaging algorithm in particular also has a pesky global softmax operation, and I used tricks similar to FlashAttention2 to minimize HBM accesses. Removing these bottlenecks has helped them feasibly scale their models on more data!

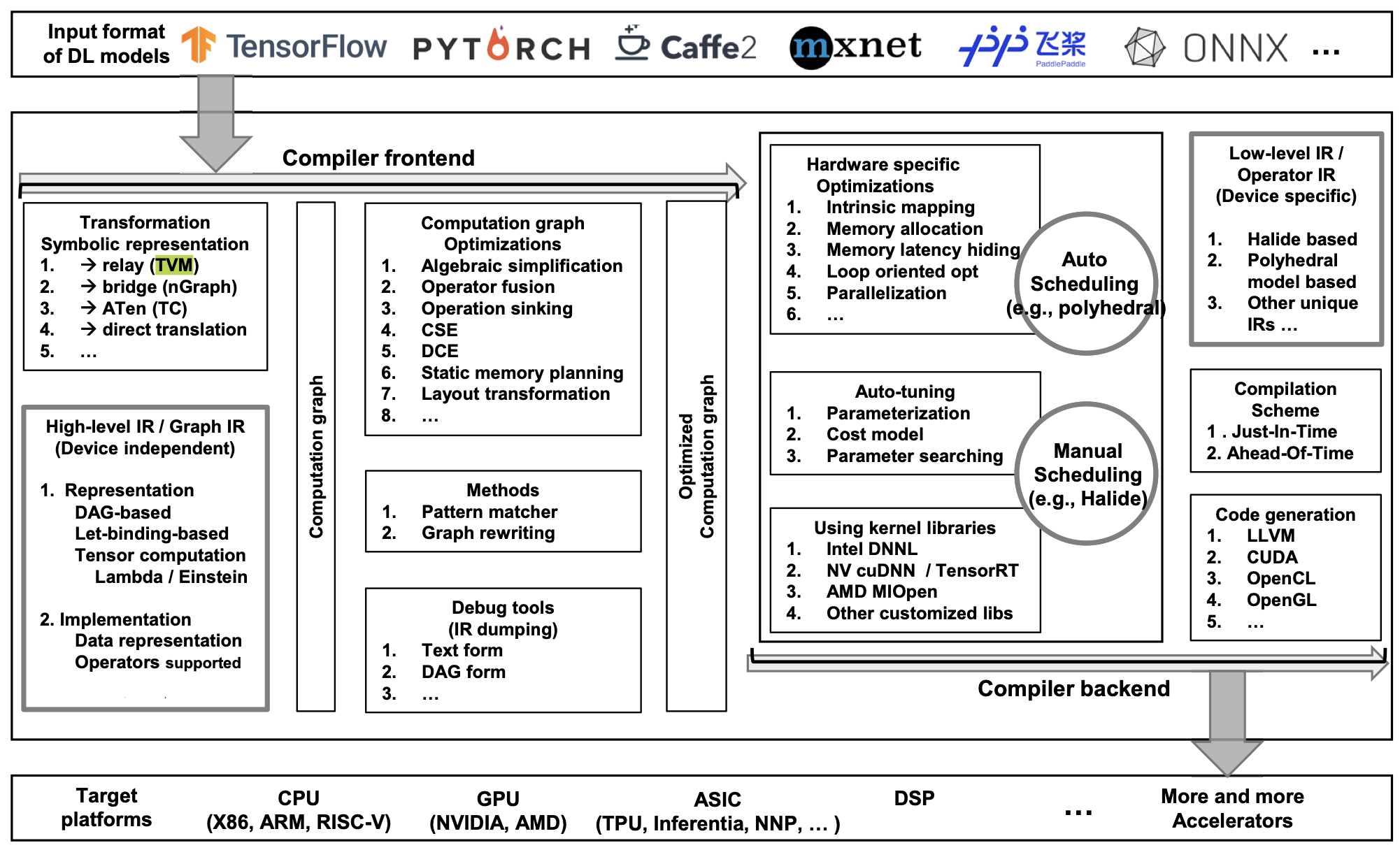

III.1.e: Deep Learning Compilers

Another parallel thread that the community was interested in was building specialized compilers

Intermediate representations (IR) are a critical element of modern compilers — instead of building a compiler for each pair of (language, hardware), we would ideally like to compile each language into a common intermediate language that can be converted to each specific machine code. Deep learning applications are typically optimized in two steps, namely graph-level optimization of operators, and low-level optimization of the actual device-specific instructions. Below, we discuss some important frameworks and compilers that have evolved throughout the years — the list is not comprehensive (check out https://github.com/merrymercy/awesome-tensor-compilers!), but focuses mainly on applications that have been popular for a while.

ONNX (PyTorch Team, 2017). ONNX is not actually a compiler, but an open-source standard format and inference engine (ONNX Runtime) for model computation graphs across different libraries. Most libraries allow you to export your models to ONNX, allowing you to use their optimized runtime engine, as well as convert models easily between libraries. Many of the libraries listed below accept or expect a packaged ONNX model as input.

Agnostic stacks. These frameworks are designed for developers to be able to modify and add certain parts of their compilers stack (e.g. targeting your own edge devices), and are widely used as general purpose compilers. They often features multiple IR conversion and optimization steps, and provide functionality for targeting your own hardware.

-

TVM (Chen et al., 2018

). TVM is an open-source end-to-end compiler stack for common deep learning platforms and targets a wide range of hardware. TVM first converts compute graphs into a directed-acyclic graph (DAG) IR called Relay — you may have learned about let-based IRs in your undergraduate compilers class that allow for optimizations like dead-code elimination, and a DAG IR is basically just the equivalent for a graph. The individual tensor operators have a separate optimization step, and TVM uses functional “tensor expressions” to define these operators. TVM has a ton of other really cool features like auto-tuning for specific data/hardware formats that are beyond the scope of what I really understand, but I would highly recommend reading the DL compilers survey for a high-level overview of TVM and other compilers. -

MLIR. The Multi-Level Intermediate Representation (MLIR) is an extension to LLVM

Again, sort of assuming you know what it is. In case you don’t, LLVM is a really powerful and language-independent library that features the LLVM IR. You would generally convert your language of choice into the LLVM IR, LLVM would perform a bunch of optimizations, then it would convert the IR into your hardware of choice. Before LLVM, dealing with compilers across different hardware was a pain in the ass. LLVM is also used for these deep learning compilers as well. that essentially allows you to define your own IR / dialect based on existing MLIR dialects — in other words, you don’t have to define an IR completely from scratch. MLIR is extremely useful in the context of deep learning compilers, because we often care about multiple optimization passes at different abstractions, which MLIR gives you the flexibility to define. MLIR works well with a lot of the compilers / tools we will list below — to get started, I found this post pretty helpful: http://lastweek.io/notes/MLIR/.

Examples of prominent specific-compilers. These compilers are technically general-use, but are mostly used to target specific devices or specific libraries. Unlike the frameworks above, they are highly optimized for specific use-cases and are much more useful as tools rather than personal development. If you’re not very interested in compilers, it is nice to know some of the stuff listed below.

- nvcc (NVIDIA, 2007). nvcc is NVIDIA’s compiler for CUDA to PTX (NVIDIA GPU’s assembly code). As far as I’m aware, a lot of the details about how what the compiler does under the hood are proprietary.

- XLA (Google, 2017). The accelerated linear algebra (XLA) compiler is mainly for linear algebra workloads in TensorFlow/Jax. It also features a just-in-time (JIT) compiler and operates at the computation graph-level. The OpenXLA project designed it to be able to target other non-TPU hardware as well.

- TensorRT (NVIDIA, 2019). TensorRT (and now TensorRT-LLM) are inference engines that target NVIDIA devices. Given a computational graph in PyTorch/Tensorflow or ONNX, these libraries apply a set of optimizations (e.g. layer fusion, quantization, kernel selection) on CUDA devices for low-latency inference.

- PyTorch’s Compilers over the Years. PyTorch supports both eager execution and graph execution, and it compiles these separately. Recently, PyTorch 2.0 introduced the torch.compile() decorator for easily applying JIT compilation to your code (with some restrictions of course). The PyTorch umbrella includes several different compilers such as the two-phase IR Glow (2018), nvFuser (2022), and the JIT compiler TorchDynamo + TorchInductor.

-

Triton IR (Philippe Tillet / OpenAI, 2021). Triton is a domain-specific language for programming NVIDIA GPU kernels in Python

If you’ve used Triton, you’ll notice the compute hierarchy is less granular than CUDA. Kernels operates at the block level, and there are specific functions for loading memory into threads. The other downside is the reliance on the Triton compiler when new hardware comes out, e.g. targeting H100 features like the TMA. . By default, thetorch.compile()function generates Triton code using TorchInductor. Triton has its own compiler, which converts Triton code into the MLIR-based Triton IR. The Triton-JIT compiler then optimizes this code and generates PTX code. I have found Sasha Rush’s GPU Puzzles to be quite useful (my solutions). I also found the Liger Kernel repository, which we talked about earlier, to be a well-written set of examples for learning Triton.

Remark. There is honestly a lot more to talk about regarding deep learning compilers, and compilers in general, but it is hard to motivate it at a high-level without going into details. There’s also a lot that goes into the design choices for specific optimizations, and I’m really not an expert on this stuff. I linked this earlier, but I did find The Deep Learning Compiler: A Comprehensive Survey to be extremely informative on the design choices of these compilers.

Part III.2: The Era of Scale (distributed version)

Imagine that you are a {insert big tech company or unicorn startup} in 2020, and you are now a big believer in scale — you want to build, say, a trillion parameter model, but you now have a whole suite of new problems in the distributed setting. I previously mentioned adding more GPUs as an “obvious” solution to scaling models, but doing this is a lot harder than it sounds — a lot of work goes into minimizing various overheads, circumventing communication errors, and building fault-tolerant and stable algorithms for distributed workloads.

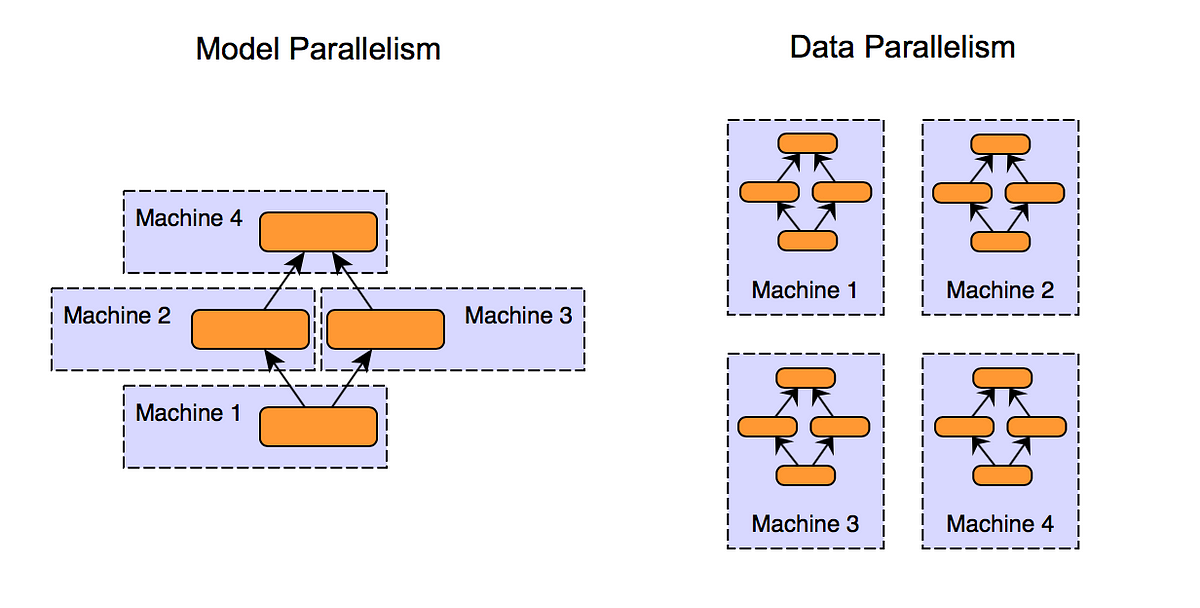

III.2.a: Data parallelism

Suppose I have a 1B parameter (~2GB) language model that I want to train on the C4 dataset (~750 GB). One common approach to accelerating training is to increase the batch size to increase the training throughput by taking advantage of the GPU’s parallelism (e.g. Llama 3 uses a batch size of each least 250K). Because we know that models make updates after batches of training, the naive approach is to put a copy of the model on each GPU and distribute the batch across multiple GPUs so it can fit in memory. Certain libraries like PyTorch have wrappers that handle distributing and gathering gradients across GPUs to make sure the model copies on each device are in sync

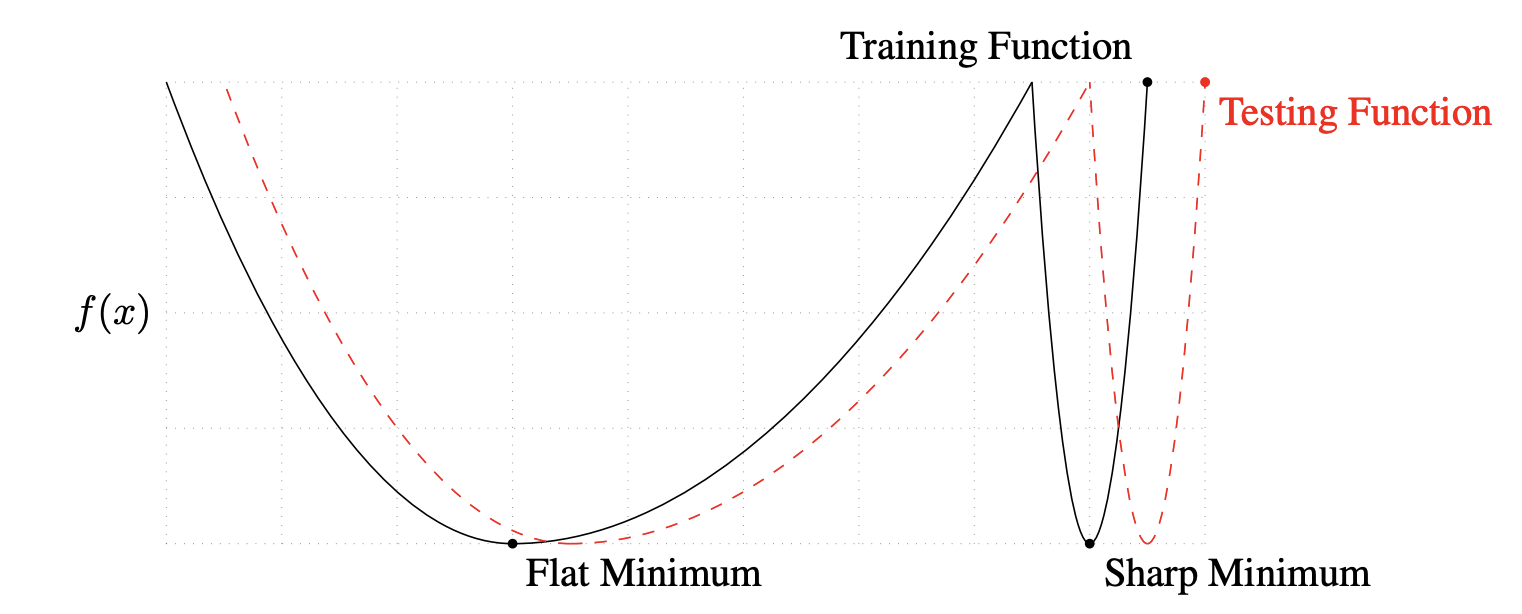

On Large-Batch Training for Deep Learning: Generalization Gap and Sharp Minima (Keskar et al., 2016

III.2.b: Model parallelism

Like data parallelism, model parallelism is not necessarily that technically novel or interesting, but it is still extremely important and relevant today. Data parallelism relies on the model (+ optimizer states and data) fitting on a single GPU, but for large models this may not be possible (e.g. 400B parameter full-precision model is ~800GB just for model weights, far too big to fit on any GPU). AlexNet, for example, split the model across two GPUs in the original implementation, as they only had 3GB of RAM. Model parallelism is far more complex than data parallelism in that there are “blocking” steps — if we have a model with layer A which goes into layer B and we put the layers on different devices, we have to wait for layer A to finish before starting computation in layer B.

Mesh-Tensorflow (Shazeer et al., 2018

Another similar term you will probably see a lot is “tensor parallelism”, and it’s basically a form of model parallelism where we partition the weights of a layer along a particular dimension and place them on different devices. Megatron-LM, which we talk about in III.2.d, relies heavily on tensor parallelism.

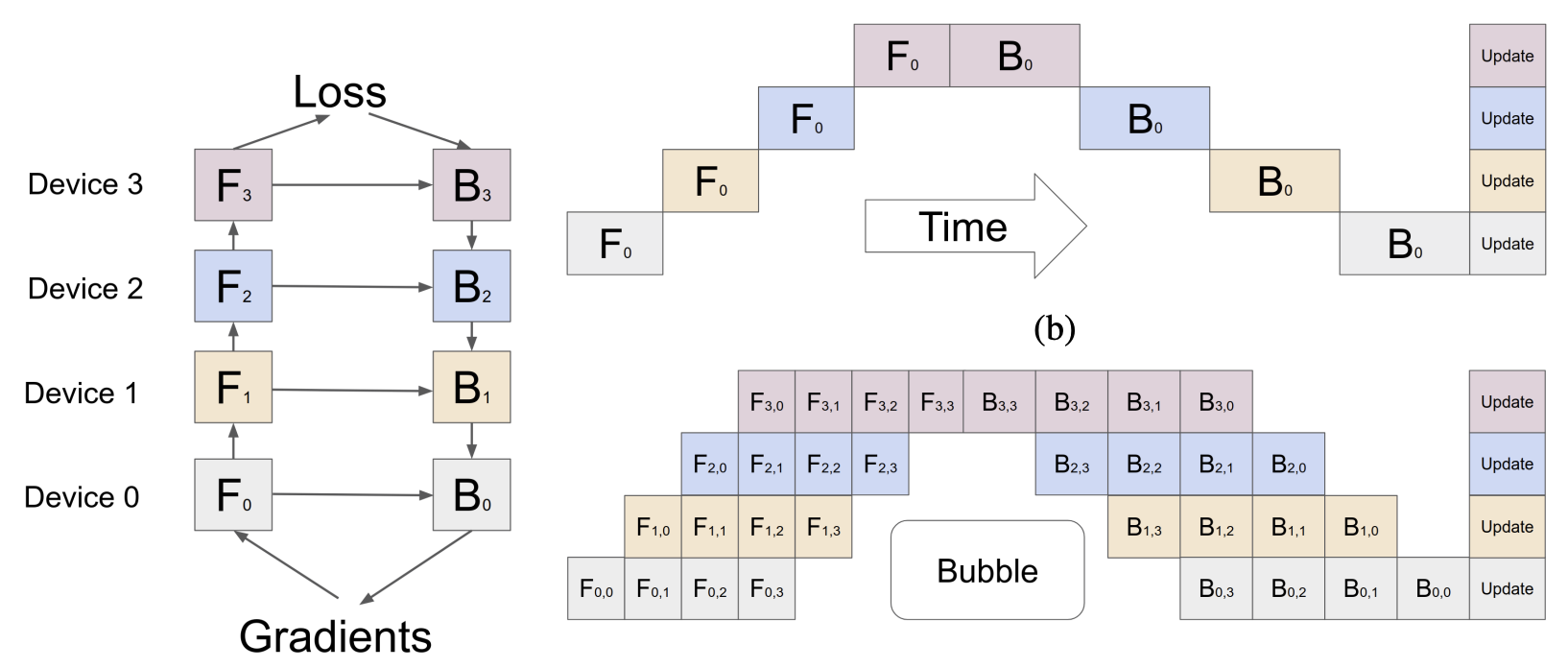

III.2.c: Pipeline parallelism

Model parallelism & Mesh TensorFlow suffer from significant downtime when dependencies are involved. For example, if we split a model into layer A and B, where the output of A is the input of B, the devices holding layer B are blocked until layer A is finished. Pipeline parallelism is basically like pipelining in computer architecture — we pass partially computed tensors to satisfy dependencies, while also keeping GPU utilization high.

G-Pipe (Huang et al., 2018

PipeDream (Narayanan et al., 2018

Some other follow-up works like PipeDream-2BW (Narayanan, 2020) and WPipe (Yang et al., 2022) essentially minimize the stall / bubble time of the above methods, but are far more specific and still use the core idea that G-Pipe and Pipedream proposed.

III.2.d: Architecture-specific Parallelism

This mini-section is somewhat overlapping with the previous two, as model and pipeline parallelism are not necessarily architecture-agnostic. It should be pretty clear that there are certain considerations like load balancing and how to partition the model that are difficult to optimize when the model architecture is unknown. There are many recent works that focus on parallelizing specific architectures for scale, especially transformers.

Megatron-LM (Shoeybi et al., 2020

III.2.e: Multi-node distributed training

We can generally get away with multi-GPU workloads on a single node (e.g. a DGX A100 8x80GB server) without having to deal with a scheduling algorithm or factoring node-to-node network bandwidth as a bottleneck, but as we start scaling even further to pre-training foundation models, we have to consider multi-node multi-GPU training frameworks.

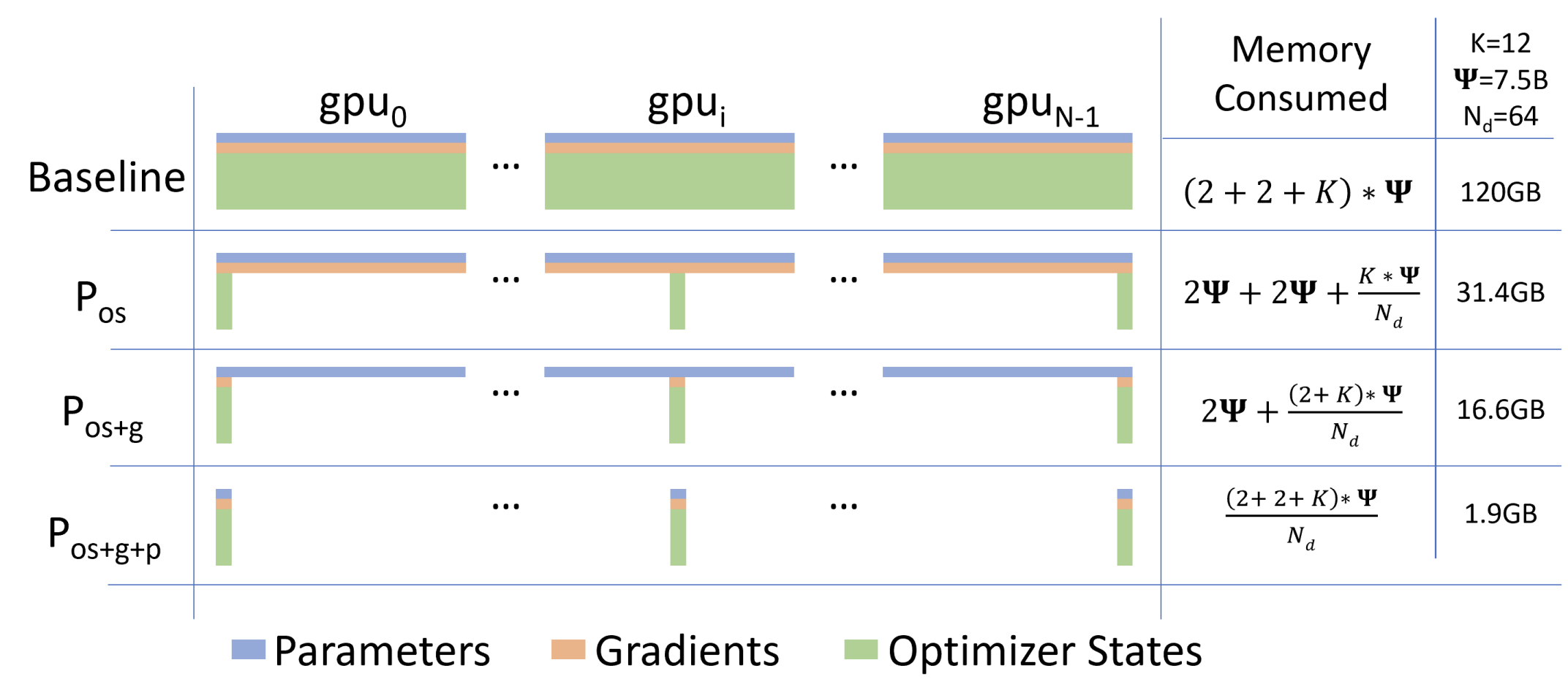

ZeRO (Rajbhandari et al., 2020

- ZeRO-DP targets various types of memory such as optimizer states (stage 1), gradients (stage 2), and the actual parameters of the model (stage 3). The general strategy is for each device to be responsible for holding and updating a partition of these components in memory, while requesting certain partitions only when needed (updates are made with a final all-gather or reduce-scatter). For example, when partitioning the model parameters, instead of performing model parallelism, where layer A sits on device 1 and sends its outputs to layer B on device 2, device 1 will instead grab layer B from device 2 and compute it all on device.

- ZeRO-R also centers around the partitioning strategy, but instead patches up a lot of the potential redundancies caused by ZeRO-DP. ZeRO-R handles activation checkpointing with a partitioning strategy similar to those found in ZeRO-DP (basically request it when you need it), but also uses a buffer to ensure requests are sufficiently sized while also handling memory fragmentation by pre-allocating contiguous memory chunks as needed.

There are a lot of rich details regarding how each optimization is ZeRO is implemented using node communication primitives that can be found in the original paper. ZeRO has since evolved into a family of optimizations for multi-device deep learning workloads and is directly usable with multi-device deep learning libraries like deepspeed.

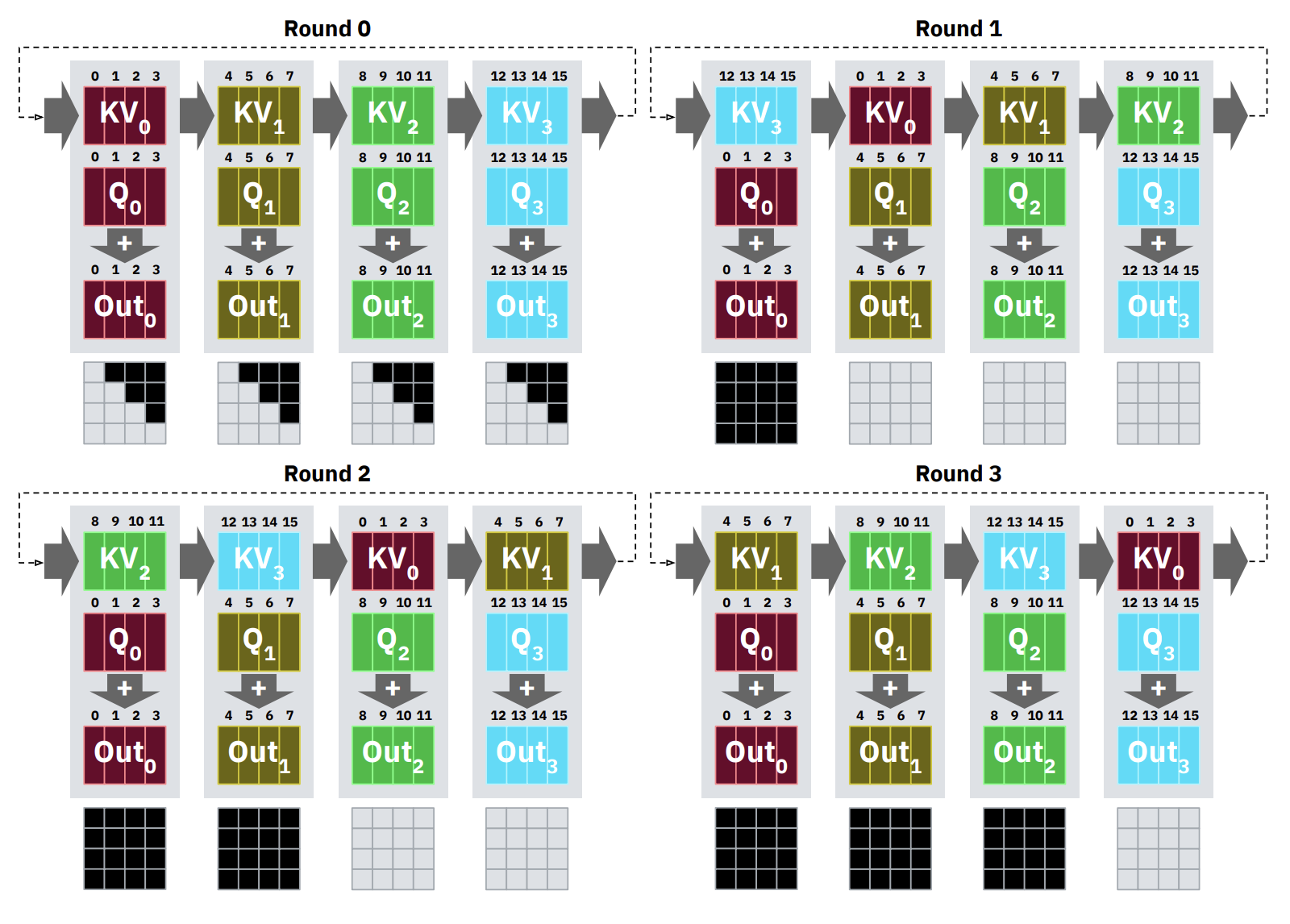

RingAttention (Liu et al., 2023

StripedAttention (Brandon et al., 2023

III.2.f: Libraries for distributed deep learning workloads.

Multi-GPU and multi-node algorithms like ZeRO have been integrated into libraries for developers to use. The community has moved extraordinarily fast on producing libraries for multi-device training and inference, making it possible for people with no knowledge to use multiple devices. In this section, I want to talk a little bit about those libraries, as well as provide some context for what is going on under the hood. We begin with a simple example of how to run basic distributed training in PyTorch.

PyTorch example. In PyTorch, we start by initializing a process group on each device that defines a master address/port, its device rank, the world size, and a communication backend.

- The master address and port from the master node, which generally controls the whole distributed system, is set across all nodes.

- The device rank or world rank is a unique identifier in $\mathbb{N}$ for each device in the distributed network. The local rank is the identifier of a process within a node (e.g. gpu:0), and the world size is the total number of devices.

- The communication backend is the protocol that defines how messages are sent and received across nodes and devices, as well as the available communication collectives (e.g. send, recv, all_reduce, all_to_all, reduce_scatter, etc.).

Modern libraries like deepspeed will make these primitives a lot easier for you, and will even make launching these applications with their CLI tools a lot simpler (you’ll probably just have to run deepspeed program.py ...). If you were to manually run a distributed workload (e.g. with PyTorch’s DistributedDataParallel or by defining your own sends and receives), you would typically have to run the program on each separate node while specifying their individual ranks.